ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on the challenges associated with teaching international students along with strategies that could help meet these challenges. The collective experience of the authors dealing with international students at the tertiary level have been the basis of this article. Among others, an absence of motivation for learning due to the negative valence for the outcome (i.e., the perceived absence of value students attach to the outcome) seems to have been a major impediment. Financial predicaments and lack of work-ready skills also make it harder for international students. Kolb (1984) and Gibb’s (1988) models have been considered to improve students' learning outcomes. Recommendations include developing a scheme to provide funding like FEE-HELP, allowing flexibility in terms of time taken to complete a degree, overhauling curricula to incorporate the skills required for job readiness, and providing additional support for students. This will require thoughtful and collective efforts from major players in the sector including the government.

INTRODUCTION

Learning and teaching (L&T) is as old as human civilisation. Ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians are among the finest earliest examples of institutionalised teaching and learning. The 'Academy' (as it was called) that was founded by Plato educated Athenian young adults for a lengthy period. In some form or other it remained in existence from 387 B.C. to A.D. 529 (Kreis, 2009). Today’s teaching and learning no longer takes place underneath the shade of trees as it used to be in ancient times, but the fundamental premise of L&T remains the same. Modern day L&T (except for last few years due to the onslaught of COVID-19) is taking place inside lecture rooms equipped with state-of-the-art technology. Until the recent past, 'Chalk and talk' was the main tool in this regard. ‘Talk’ still plays the predominant role in L&T but the ‘chalk’ has been long gone with the evolution of computerised and more interactive tools such as SMART Boards. Use of computers and online facilities in L&T is widespread. Even though the L&T tools, techniques, and environments in today's world (particularly in Australia) are far more sophisticated - it still makes one wonder whether international students are acquiring the knowledge required and mastering the skills needed to become productive members of the 21st century workforce in Australia or the equivalent somewhere else.

A three-year study conducted by Deakin University concluded that despite having qualifications in areas of skills shortages in Australia, international students found it difficult to get professional work after graduation. The study highlighted poor communication skills, lack of teamwork ability, and lack of work experiences as some of the main reasons (Blackmore et al., 2014). These realities (along with unrealistic student expectations) place challenges on the role of the frontline academics dealing with international students. Gribble and Blackmore (2012. p. 350) suggested that some form of ‘work integrated learning’ combined with an ‘opportunity to contextualise’ knowledge gained via education might help alter employers’ reluctance in recruiting international students after graduation from an Australian institution.

OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this paper is to identify the challenges associated with teaching international tertiary level students studying business courses with the private and semi-private providers in Australia. The focus is on students coming from Asia. The paper further aims at exploring the possibility of ameliorating those challenges by applying some existing learning models and techniques.

METHODOLOGY AND LIMITATIONS

This is a case-study-based paper. The collective decades of firsthand experience of its authors in dealing with international students in Australia has been the main springboard in preparing the paper. Information gathered via surveys conducted at different points by the authors and by other researchers in the recent past, for various other reasons, have also been used here. The paper further utilised relevant learning and teaching theoretical models, concepts and strategies wherever deemed necessary. The focus of the paper is narrow and therefore it cannot be considered as representative of the entire sector.

CHALLENGES

According to the Department of Education, Skills, and Employment (2019), pre-COVID-19 - there were 758,154 enrolments of full fee-paying international students in Australia on a student visa and 46.2% of these students were in the higher education sector. This represented a 9.7% increase from the previous year. Nearly 58% of these students were from China (37.3%) and India (20.5%).

COVID-19 changed almost everything. It forced human society to accept the ‘unacceptable’ with regard to many things in life. From a terrifying and confused state, COVID-19 has driven us to a new realisation about life and livelihood. Hence, it is natural to enquire if and how it has affected the tertiary teaching grounds and their associated challenges.

Research has indicated that a high percentage of international students face multifarious difficulties and challenges with socio-cultural adjustment, language, educational expectations, and norms (UniSA, 2014). These students are also required to deal with intellectual and financial challenges which interfere with and impact on their capacity to engage with their academic work. The teaching styles, approaches and learning context are often quite different in Australia to what the students have experienced in their home countries. This has an adverse impact on their academic life and progress.

These problems are not unique to international students. But compared with their domestic counterparts, the impact of the problems is disproportionate for international students because it is not easy for them to access the support that would help them to solve these problems. Their circumstances are more easily affected by academic staff, education agents, government policies, educational institutions, family, friends, and at times the students themselves.

Educational expectation is another issue. The Australian Education System places great emphasis on the skills associated with the higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (1984) that is - problem solving, critical analysis, confidence in communication, and independent and autonomous learning. This is in stark contrast to what students from Asia have been used to. Their experience of learning is quite different to those in the Australian education classroom. Most of the international students are only used to their country’s traditional style of learning. Many of the expectations/impressions that have been created in the minds of the students by the reading of the 'marketing hype' prior to embarking on the journey are often not met by the reality. According to Krause (2005), engaging in class is a battle for these students. It would require them to unlearn decades of learning habits - i.e. to let go of long-held beliefs and approaches to learning to progress in their academic life. Without a supportive and care-free environment these students will obviously struggle. Krause (2005) further suggests that the academic staff provide an environment that is both intellectually balanced and supportive.

The issue that challenges academics teaching international students most is that for many students their studies are not the primary motivation for their enrolments. The internal motivation towards learning is missing! This has a major impact on their engagement in the classroom as well as on their ability to remain engaged throughout the study program (Uddin, 2021). With regards to their financial obligations, most of the students are working long and late hours, often with less money. This impinges further on the time that can be allocated to their study. During the COVID-19 period, international students were forced, allowed, and at times even lured to work more hours. This has further exacerbated the situation.

Many students manage their initial tuition fee and travel costs with money that has been either borrowed from their parents or from non-conventional sources with high interest rates or arranged after disposal of the family’s last assets. Many such students are legally obliged to repay their educational loans very quickly, which they commit to when coming to Australia for studies, irrespective of their income situation. There is no income threshold after which the repayment kicks in. The situation gets more pressing when some families demand quick financial help from their children who are studying abroad. Some students find themselves in even harder financial situations as they have their primary or secondary school-aged young kids and/or partners living with them in Australia. These students are required to earn money to pay their kids’ school fees as well. This is simply a double jeopardy and has the potential to take a student to breaking point. The authors of this paper have first-hand experience of seeing this unfortunate, heart-throbbing saga. Financial hardship is therefore a huge challenge for international students.

This type of situation pushes academics into unknown territory. At times, teachers become simply helpless as they do not know how to manage such emotionally charged situations. This is quite taxing on their already-stretched time schedules, especially if they are working as sessional lecturers. A different type of challenge has also been brewing for quite some time. This is about academic integrity relating to allegations of outsourcing the assignment writing (contract cheating) activity by students in several Australian universities (TEQSA, 2015). Reports indicate that this is mostly a practice that is adopted by international students. Here the academics are on the frontline too. The situation often demands the academics to undertake detective work to decide on plagiarism/merit of the work. And it is not a pleasant situation. Finally, large cohorts of international students’ main motivation is not, arguably, getting education, but instead any degree that will open the doors to Australian citizenship.

If educators and institutions can get the recipe right, then some of these difficulties might be overcome.

RELEVANT CONCEPTS AND MODELS RELATING TO L&T

The problems mentioned above cannot be solved quickly or completely. Moreover, the solutions do not depend on any one person, organisation, or group. The situation will require a long hard look and a concerted effort from all parties. The academics who are inseparably involved in the process will never be able to run away from the situation. They will have to play their parts whatever they might be. Existing L&T models and concepts are likely to be of some help in this regard. However, all concerned parties will be on the look-out for better, longer-lasting, and more effective solutions.

Reflective practice is an important strategy that involves 'learning from experience'. It has been defined by Schon (1983) as the capacity to reflect on action and to engage in a process of continuous learning. It is a valuable tool for promoting autonomous, self-directed, and practice-based learning. It allows individuals to learn from their own experiences - professional or otherwise - rather than rely solely on theories. Bolton’s (2010) interpretation is that it involves paying critical attention to the practical values and theories that inform everyday actions by examining practice reflectively and reflexively.

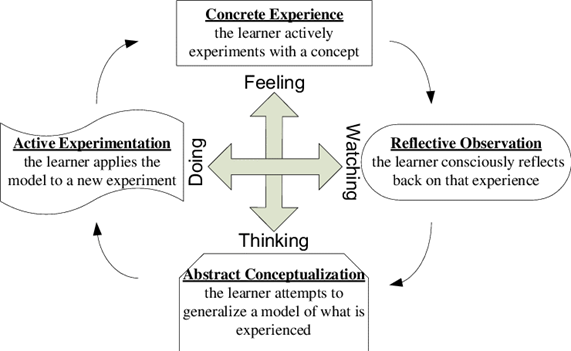

Kolb (1984), with the help of a simple circular diagram (model), has explained how an experience gained via actual involvement in a situation can help develop perceptual concepts in the minds of the participants. The concepts developed in this manner will then 'guide the choice of new experiences'. Kolb's experiential learning model suggests that 'an individual will progress and develop if there are opportunities to learn things effectively, perceptually, symbolically, as well as behaviourally.’ Which means experiential learning progresses via four connected modes and this type of learning requires four distinct kinds of abilities (Atkinson & Murrell, 1988; Sugarman, 1985).

Kolb’s experiential learning model

Source. Konak et al., 2014.

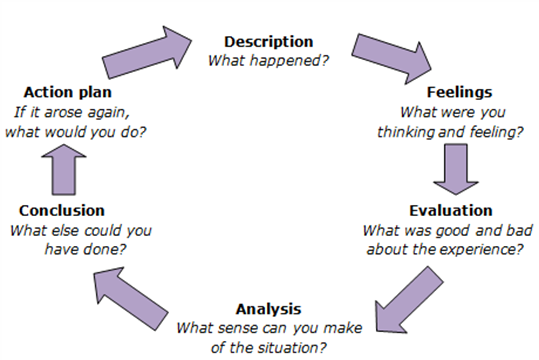

Gibbs (1988) suggested a six-stage model focused on reflection. It is a refinement of Kolb's (1984) Experiential Learning Cycle model. This model includes:

Gibbs’ reflection model

Source: Gibbs’ (1988) reflective cycle

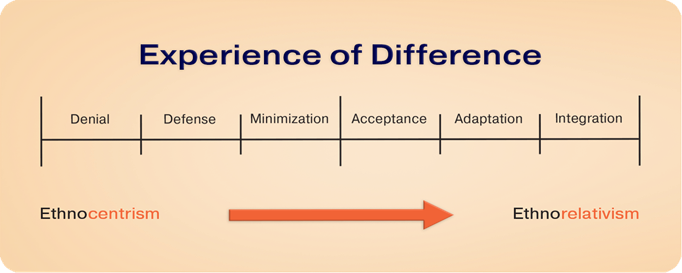

Bennett's Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS)

Source. DMIS Model - IDRInstitute. Retrieved on 4 October 2022 from https://www.idrinstitute.org/dmis/

Bennett (1993) developed his continuum model in the late 1980s to explain the change in perceptions when one interacts with different cultures. According to Bennett, perceptions move from an Ethnocentric focus to an Ethno-relative focus.

Ethnocentric stages

Ethnocentrism assumes that "the worldview of one's own culture is central to all reality" (Bennett, 1993, p. 30). The first stage of ethnocentrism is DENIAL where one just ignores the cultural differences by either isolating themself, living with their “own people”, or intentionally separating themselves to protect their world view. The next DEFENCE stage is when one sees the world as "us and them" and sees ‘us’ as superior. During the MINIMISATION stage, one can ignore the cultural differences and believe “we are all humans”.

Ethno-relative stages

Ethno-relative stages suppose that "cultures can only be understood relative to one another, and that particular behaviour can only be understood within a cultural context" (Bennett, 1993, p. 46). Ethno-relative stages start with ACCEPTANCE of cultural differences and respect of these differences. This is the stage where one usually starts making friends from diverse cultures. ADAPTATION stage is the stage where one starts showing empathy toward diverse cultures. Cultural understanding and communication can be focused on during this stage. This stage also comes with acceptance of more than one world view. At INTEGRATION stage one will feel as not belonging to any culture. Integration can be close to assimilation.

This theory is useful for understanding students’ perceptions about Australia and different cultures when they start their studies in a new country, probably often the first time they are away from their families and friends.

Reflective practice cycle- a modified model

The reflective practice cycle is an important means for continuous learning and development. The above-mentioned models, with slight modification, can be used to systematically investigate the issues raised in the 'challenges' section of this paper. It might help in enhancing understanding about the phenomena and showing some ways to improve the situation.

Modified Model

Record (What -Description): Most of the aforementioned-challenges are formidable obstacles and therefore cannot be ignored. An orderly description and categorisation of the challenges is therefore necessary for the execution of the subsequent steps in this model. The perceived challenges include:

- motivational (extrinsically driven);

- financial (precarious situation);

- language and communication (lack of proficiency, hence not much control over it);

- cultural (not like home - things are different);

- day-to-day living ('do-it-yourself' mode- never used to be like this);

- accommodation (often crowded and squalor);

- procedural (from one big annual exam, no assignment and no group work to ongoing progressive assessments and presentations);

- pedagogical (from teacher-driven to learner-centric);

- emotional (all alone - away from family and friends);

- mindset (complacency).

Reflect (Think- possible reasons). On the spur of the moment, one would think that the possible reasons for students’ inability to learn better include: misleading information from agents and marketing people; late enrolment; irregular attendance; coming late to class and leaving early; lack of reading materials; coming unprepared to class; lacking motivation; and being fresh graduates with no real-life industry experience.

Analyse- sense making of the situation (Explain and gain insight- what have been the contributing factors?): Vested groups and their interests; visa not being issued on time; could not enrol on time due to finance being not ready (continuing students); not clear-cut communication about enrolment deadlines; casual attitudes; work, family and other commitments; complacency; books and other reading materials being too expensive; push-factors (i.e., no intrinsic motivation for study); too busy working to meet financial obligations; no direct links between the study program and what is at the back of their mind as their ultimate goal (permanent residency); studying not for themselves but for their parents (extrinsic motivation); too much content to cover (not manageable); boring delivery- contents not being contextualised; and mechanistic and inflexible course designs.

New Action based on learning through the above process (What should be done to bring about change): Institutional policies and procedures addressing shortcomings; pre-departure intense briefing and thorough orientation after arrival; provide incentives to be in the classroom; online discussions; soft copy resources; hands-on class activities; blended mode of delivery; books exchange service and facilities on the premise; tailor-made reading materials (online) with publishers; out of class consulting; and discussion forums for collaboration and communication outside the class.

RECOMMENDED STRATEGIES

International students’ problems (financial, accommodation, relationships, and academic progress) are manifold and of greater magnitude than those of domestic students. All pertinent parties to an extent have been responsible for the situation. Therefore, there is a need for a coordinated approach and strategy to address it.

One way of overcoming the financial challenge could be creating a fund for international students like HECS-HELP. Unlike HECS, students could be repaying the loan taken from the fund as soon as they earn irrespective of the size of their earnings. The main aim would be to allow international students to not over worry about their finances. The pressures of refund would be less severe than in the existing situation.

Another option worth considering for full fee-paying international students would be to allow them to work fulltime during one semester and study the next for the entire duration of the study program. This would allow students to earn money - in some cases, sufficient to cover all their expenses. Another benefit of such an option is that it would familiarise international students with the Australian work environment and work culture.

Educational institutions need to get the environment right. Learning and development environments are changing. Current trends in university education such as flexible learning, flipped classes, and adoption of new technologies have started creating 21st century learning spaces where students can play, learn, and experiment. Such learning playgrounds also inspire students to be entrepreneurial and to push their limits for creativity and innovation. COVID-19 has been an incredible catalyst for this change.

Kolb (1984, p. 41) defines learning as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Knowledge results from the combination of grasping and transforming experience.” These new learning playgrounds help students to both grasp information and transform this learning into experience. This 21st century learning is also aligned with many private university strategies to graduate “work-ready” students as well as TEQSA’s Provider Standards to craft future workforces (Coates and Mahat, 2014). For a learning space to be aligned with Kolb's Learning Model, it has to offer students the opportunity to engage fully in the four stages of the learning cycle: feeling, reflection, thinking, and action. A supportive and at the same time challenging learning playground can create the right environment for repetitive practice for students as well as intrinsic motivation to play, learn and experiment (Kolb & Kolb, 2010).

Application of the Kolb model can lead to the development of strategies that make international students work-ready. By increasing the student’s employability, these strategies would increase the student’s engagement in classes. It may be argued that it is the academic’s role to only engage the student in academic pursuits and not in the development of their employability skills. But it must be an imperative to make students realise the value of their Australian education too. Most international students do not think of their employment in their chosen profession until they are in their last year of study, and hence have not done enough to make themselves work-ready. The report by Deakin University (2014) on Australian international graduates and their transition to employment highlighted the importance of work-integrated learning for international students. Experiential learning through internships and work placements has not been prioritised currently due to the pressure of combining study with part time work to cover day-to-day living expenses. However, this should be made an important part of the curriculum for international students to make them work-ready. This requires a combined effort from the academics through curriculum development as well as from the institutions and industries through framing enabling policies.

Australia’s multicultural nature creates challenges and advantages both for workplaces and universities. Jackson’s (1995) study shows great differences in learning preferences between different European nationalities. The study creates national cultural profiles of some European countries for learning and suggests Anglo-Irish, Spanish and East Europeans prefer Kolb’s own intuitive approach whereas French and German students have shown a preference for moderate direct control from lecturers. Research in this area focuses on certain nationalities (such as Jackson’s study between European countries) and it would be interesting to see the results of a large-scale research that can reflect the true nature of Australia.

Bennett’s (1993) Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) can be used to understand students’ perceptions about Australia and diverse/unfamiliar cultures. Institutions and lecturers can be more useful to students by knowing which stage they are currently in. It is also possible to develop students’ intercultural competence and help them to adapt to their new lifestyle and highly valued Blooms Taxonomy skills faster. A study at the Universidad Popular Autónoma del Estado de Puebla (UPAEP) proposed the development of a program that included activities that would raise their undergraduate students’ level at least to the acceptance level of the DMIS continuum. Research by Fabregas Janeiro, Fabre and Nuño de la Parra (2014, p.15) shows that, as a result of including these activities, “students have attained a high level of skill in knowing their own culture, cultural differences, and engage in respect for people from other cultures”. This study also emphasised the importance of initial stages of the continuum and suggested continued coaching during the continuum.

CONCLUSION

The challenges raised in this article cannot be resolved overnight but the situation would likely improve with the implementation of the strategies discussed. This would be an on-going process to ensure sustained progress. Other things remaining the same, the reflective practice cycle is a useful tool for effective learning and development.

REFERENCES

Atkinson, G. Jr., Murrell, P. H. (1988). Kolb's Experiential Learning Theory: A Meta-Model for Career Exploration. Journal of Counselling & Development, 66(8), 374-377.

Bennett, M. J. (1986). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 10, no.2: 179-95.

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethno-relativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity (revised). In R. M. Paige (Eds.), Education for the Intercultural Experience. Yarmouth, Me: Intercultural Press.

Blackmore, J., Gribble, K., Lesley, F., Rahimi, M., Arber, R., Devlin, M. (2014). Australian International Graduates and the Transition to Employment, Deakin University, viewed 18 September 2022. https://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/365194/international-graduates-employment.pdf

Bloom, B. (1984). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA

Bolton, G. (2010). Reflective Practice, Writing and Professional Development (3rd edition), SAGE publications: California, USA

Coates, H. & Mahat, M. (2014). Threshold quality parameters in hybrid higher education. Higher Education, October, 68(4), 577-590.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment, (2019). End of Year Summary of International Student Data 2019. Australian Government. Retrieved from https://internationaleducation.gov.au/research/International-Student-Data/Documents/MONTHLY%20SUMMARIES/2019/December%202019%20End%20of%20year%20summary.pdf#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20there%20were%20956%2C773%20enrolments%20generated%20by,10.3%25%20per%20year%20over%20the%20preceding%20five%20years on 18 September 2022.

Fabregas Janeiro, M. G., Fabre, R. L. & Nuño de la Parra, J. P. (2014). Building Intercultural Competence Through Intercultural Competency Certification of Undergraduate Students. Journal of International Education Research, 10(1), 15-22.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford: Further Education Unit, UK

Gribble, C. & Blackmore, J. (2012). Re-positioning Australia’s international education in global knowledge economies: implications of shifts in skilled migration policies for universities. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34(4), August, 341–354.

Jackson, T. (1995). European management learning: A cross-cultural interpretation of Kolb's learning cycle. The Journal of Management Development, 14(6), 42-51.

Kolb, A. Y. & Kolb, D. A. (2010). Learning to play, playing to learn: A case study of a ludic learning space. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(1), 26-50.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: experience as a source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Konak, A, Clark, T. K. & Nasereddin, M. (2014). Using Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle to improve student learning in virtual computer laboratories. Computers & Education, Vol 72, March, 1-22

Krause, K. L. (2005). Understanding and promoting student engagement in university learning communities. Viewed May 14th, 2015, from University of Melbourne - Centre for the study of Higher Education: https://cshe.unimelb.edu.au/resources_teach/ teaching_in_practice/docs/Stud_eng.pdf

Kreis, S. (2009). 'Greek Thought: Socrates, Plato and Aristotle', Ancient and Medieval European History. Retrieved 5 December 2015 from http://www.historyguide. org/ancient/lecture8b.html

Schön, D. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner, How Professionals Think In Action. Basic Books

Sugarman, L. (1985). Kolb's Model of Experiential Learning: Touchstone for Trainers, Students, Counsellors, and Clients. Journal of Counselling & Development, 64(4), 264-268.

TEQSA, (2015). Report on student academic integrity and allegations of contract cheating by university students. Australian Government. Retrieved from http://www.teqsa.gov.au/news-publications/report-student-academic-integrity-and-allegations-contract-cheating-university on 7 November 2015.

University of South Australia, (2014). Teaching in Higher Education. L & T Unit. Retrieved from http://w3.unisa.edu.au/academicdevelopment/diversity/international.asp on 11 Dec 2015.

Uddin, S. J. (2021). Enhancing student engagement? Let’s get real! In A. Hooke & G. Whatley edited Updating and Enhancing Course Content, Course Delivery, and Academic Management. Vol. 2, Group Colleges Australia Pty Ltd. Sydney 75-83.

BIOGRAPHIES

Assistant Professor Dr. Syed Uddin lectures in Business Management, Human Resource Management and Organisational Behaviour at UBSS. Formerly, he was a Research Fellow at the Loughborough University Business School in the United Kingdom. He has written many refereed articles that have been published in prestigious academic journals. Syed is a six-time winner of the UBSS Executive Dean's award for 'Outstanding Commitment to Teaching and Learning' and is a recipient of the Vice Chancellor’s Citation Award for outstanding contributions to student learning.

Ozge Fettahlioglu is an entrepreneur, educator, and home design enthusiast who believes everyone deserves a happy place to live in. She currently manages a renovation company called Boxareno, a restaurant, a café, and an e-commerce homeware business. She developed course content and worked as an educator for business subjects at UNSW, was a lead lecturer in many universities, and recently designed and lectured on business subjects for a WSU 21st century flagship program for Master in Project Management – Construction.

Dr. Nilima Paul is Assistant Professor in Accounting at UBSS. She has Bachelor of Commerce (Honours) degree, a Graduate Certificate in Tertiary Education, a Master of Commerce degree, and a Doctor of Philosophy degree. Nilima is a member of the National Tax and Accounts Association, the Australian Institute of Training and Development, and the Association of Accounting Technicians. She has been teaching accounting to undergraduate and postgraduate students in a range of universities and colleges for more than 30 years and has won numerous awards for her commitment to teaching and learning.

Divya Judge is a lecturer at the College of Leadership and Business (COLAB). She holds an MBA in International Hospitality Management from Schiller University in London and an MBA with a specialisation in Marketing and Human Resources from India. Divya has over 25 years of experience lecturing in Graduate and Undergraduate Business courses in Australia, Singapore, and France. She has also won several teaching commendations and awards over the course of her academic career. In her free time, Divya loves to read (non-fiction and crime stories) and travel.