ABSTRACT

The concept of culture includes social norms. These are often influenced by sudden unexpected events and the reactions to these events. COVID-19 is one of these events. This article explores some impacts of COVID-19 on cross-cultural behaviours due to social behavioural changes and government responses to the Pandemic. It focuses on the impacts of cross-cultural actions on ‘mask-wearing’, ‘social distancing’, ‘vaccination’, ‘marital relationships’, and ‘attitude towards life’. The analysis adopts the Williams (1960) definition of culture as ‘a way of life’. The authors argue that social norms are dynamic and changing and that the COVID-19 Pandemic has on-going implications for our future way of life.

INTRODUCTION

The unprecedented and ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic has had an enormous impact on cross-cultural behaviours in all aspects of life due to its sudden changing of the living environment (social, economic, political, and cultural). The question we try to answer in this article is: How did the Pandemic impact on people’s way of life and how did people react to the impact in different cultural contexts? According to Adler et al. (2011, p.2), from the view of anthropologists “… cultures provide solutions to problems of adaptation to the environment”. Therefore, culture cannot be regarded as a set of static elements or social norms embedded in societal and individual behaviours. The authors have observed that one particular behaviour that was unacceptable pre-COVID-19 has become an acceptable social norm now across different cultures.

DEFINITION OF CULTURE RELEVANT FOR THE STUDY

Culture incorporates a variety of elements and is defined from various perspectives across academic disciplines. UNESCO (2001) defines it as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society or a social group, which encompass, in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs. UNESCO’s definition is too broad for this study.

After canvassing more than 150 definitions from different disciplines, the 1952 definition by Kroeber and Kluckhohn stands out. They argue that culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit, of and for behaviour acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups, and including their embodiments in artifacts. The essential core of culture is traditional (i.e., historically derived and selected) ideas and especially their attached values. Culture systems may, on the one hand, be considered as products of action; and on the other hand, as conditioning elements of further action (Baldwin et al. 2006 pp. 8-9). This definition constitutes a set of basic cultural elements that is accepted by scholars across many academic disciplines.

However, for this study, the definition by Raymond Williams (1960) is the most suitable. Williams stated that “culture is not only a body of intellectual or imaginative work - it is also and essentially a whole way of life”. The term ‘way of life’, however, has different interpretations and meanings in different social contexts. Cronk (1999), extracted some key elements from almost 20 definitions (Baldwin et al., 2006), noting that everything that people have, think, do, make, and believe together with people’s ideas, behaviours, and ways of life as members of a society, are considered - culture. This is a concise explanation of what culture is about and where it comes from.

Despite some critiques, Geert Hofstede’s concept of cultural dimensions is a practical and popular approach in the field of culture and cross-cultural management studies. It focuses on six dimensions (Browaeys and Price, 2019) including ‘power distance’ (high/low), ‘uncertainty avoidance’ (high/low), ‘individual vs group orientation’, ‘masculine vs feminine orientation’, and ‘short-term vs long-term orientation’.

Harry Triandis (2002), a contemporary cross-cultural anthropologist, made a valuable contribution to the literature by categorising and distinguishing between the concept of material (objective) culture, which includes things like dress, food, house, and machines (artifacts), and subjective culture - the systems of economic, social, political, and religious beliefs and behaviours. He described subjective culture as “a society’s characteristic way of perceiving its social environment’ (Triandis, 2002, p.3).

In this study, the definition of culture as ‘a way of life’ is employed in discussing and analysing the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on peoples’ way of life and on the responses and adaptations of society and individuals (their attitudes, behaviours, and value systems) across different cultures.

IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON CULTURE: A CROSS-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE

The ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic is a global event impacting all spheres of our life across cultures and borders as well as across societal, economic, and cultural dimensions. When the virus emerged in January 2020, few people realised that it was the start of the world’s first pandemic since the ‘Spanish Flu’ a century earlier. The latest data from WHO (2022) show that reported and confirmed COVID-19 cases reached to 651,918,402 including 6,656,601 deaths as of 23 December 2022. And, as reports from China illustrate, the Pandemic is still far from over.

The impact of the Pandemic on peoples’ lives is more implicit from the viewpoint of subjective culture than explicit from the viewpoint of objective culture. External pressures impact on cultural behaviour via ‘wearing masks’, ‘social distancing’, and vaccination outside the family; internal pressures impact on cultural behaviour via marital relationships within the family.

Reaction to ‘uncertainty avoidance’ (high vs low)

Before COVID-19, a person wearing a mask signalled to others a sign of being ‘unwell’ and ‘unwelcome’. Some individuals rejected the compulsory measure of wearing a mask in public as a violation of their ‘individual right to freedom”. Now, wearing of a mask is a preventive measure that has nothing to do with the pre-COVID-19 perception. The change in this social norm explains why most Asian people wearing a mask in the early stages of the Pandemic were not popular among non-Asian communities, but later their behaviour became acceptable, and was followed by non-Asian as well as Asian communities. COVID-19 has impacted cross-cultural behaviour by changing our reaction to ‘uncertainty avoidance’ from low to high awareness (Browaeys and Price, 2019).

Reaction to ‘power distance’ (high vs low)

Before COVID-19, ‘social distancing’ was regarded as a strange behaviour from a cultural perspective because cultural relationship is measured by the distance between individuals and social distancing represents a ‘dissocialising behaviour’. Now, people are used to the concept of a friendly norm of distancing from each other. The Pandemic has impacted cross-cultural behaviour by changing the reaction to ‘power distance’ from low to high level (Browaeys and Price, 2019).

Reaction to ‘social orientation’ (individual vs collective)

Before COVID-19, vaccinations were not generally welcomed. Rather, they were regarded as unnecessary or voluntary because vaccination was perceived as an individual sacrifice for the collective benefit. Now people have changed their attitude towards vaccination, believing that all are safe when each individual is safe. COVID-19 has impacted cross-cultural behaviour by changing the reaction to ‘social orientation’ from individual to collective (Browaeys and Price, 2019).

Studies suggest that ‘… behaviours such as mask wearing, social distancing, and intention to vaccinate are connected to collectivist mindsets or collectivistic cultures’ (Nair et al., 2022). According to Hofstede’s theory of national cultural dimensions (Browaeys and Price, 2019), the dimension of individualism/collectivism illustrates that some cultures regard personal relationships (‘I’ and individual-orientated) to be more important than collective relationships (‘we’ and group-focused). A study by Lu et al., (in Nair et al., 2022), which was based on data collected from 67 countries that included cultures of both individualism and collectivism, noted that mask wearing was more accepted in countries that were high in collectivism and less so where individualism was high. Countries like Japan, Singapore, China, and South Korea are more collectivist-oriented compared with Western countries such as the United States and most countries in Western Europe, which are individualism focused. This is reflected in the strong collective efforts in persisting in mask wearing in these collectivistic Asian countries while countries that are more individual-focused exhibited less enthusiasm in employing the same approach in the early stages of the Pandemic.

Culture (the way of life) and cross-cultural differences - whether they are at national, societal, and individual level or in different dimensions (e.g., Hofstede’s individualist vs collectivist cultural dimension) might also have experienced the same situations and changes in lockdown and vaccination practices as in the mask-wearing case discussed above. Some early studies suggested that individualistic societies showed less attention to the COVID-19 restrictions and seemingly increased the risk of virus infection while societies located in Hofstede’s higher ‘’uncertainty avoidance’ cultural dimension were more willing to follow the restriction rules and requirements (Lee et al., 2021). Apart from the cultural-dimensions considerations, Asian countries with strong Confucian values (e.g., Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore) tended to adopt the COVID-19 control measures set by their authorities promptly (e.g., mask-wearing, social distancing, social-gathering restrictions, and vaccinations) in comparison with Western countries.

Culture (the value system and belief) influences the behaviour of decision makers not only at various ‘power’ levels but also of ordinary citizens. Studies suggest that in measuring ‘promptness’ and ‘agility’ in terms of mask-wearing and other COVID-19 relevant control measures, countries like Japan, Thailand, and Taiwan were far ahead of the USA, France, and Italy in the early stage of the Pandemic (Bajaj et al., 2021).

Reaction to orientation of marital relationship (masculine vs feminine orientation)

Mass media reports indicate that behaviour in marital relationships has been impacted considerably during the pandemic. The awareness and concerns of the impact of COVID-19 on marital relations from the media are mainly based on first-hand information collected from family lawyers, couples involved in divorce proceedings, and the media. The most popular topics that have been picked up in reports and articles include how the Pandemic has strained relationships between partners (Hellyatt, 2022), has been an important cause of break-ups and divorces (Savage, 2020), has caused divorces to increase (Fitzsimmons, 2022), has produced a spike in divorces in China and around the world (Prasso, 2020), and has taken a toll on marriages in Hong Kong (Sun, 2020).

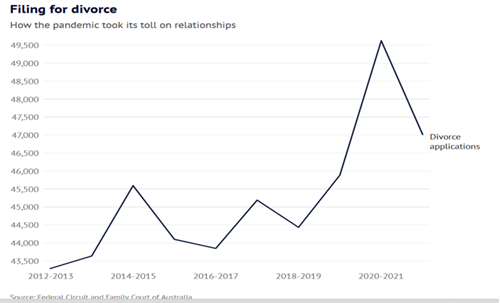

The impact of the Pandemic on the quality of marital relationships, particularly the increase in conflicts, has neither national boundaries – across from USA to China, and from UK to Australia - nor cultural barriers between ‘East’ and ‘West’. It is reported by the UK’s largest law firm that divorce inquiries during the pandemic jumped 95%. This was echoed from the other side of the Atlantic where an increase of 34% in the sales of legal forms for divorce in 2020 was reported by a law firm (Hellyatt, 2022). The same pattern emerged in Australia, where divorce applications reached a peak in the 2020 -2021 financial year of 49 625 and remained high in the following year at 47 016 (Fitzsimmons, 2022).

Source: C. Fitzsimmons, 2022

It has been reported in some mainstream media that the significant causes contributing to the changes in attitudes, behaviours, beliefs, and value systems that may lead to divorce and marriage conflicts are the stresses (financial, social, and health) derived from COVID-19 and the related safety control measures. They include frantic disagreements on childcare/parenting, sharing of housework, and other family issues that can easily lead to domestic violence (Ellyatt, 2022; Savage, 2020; Fitzsimmons, 2022; Prasso, 2020; Sun 2020). However, from a cross-cultural perspective, there is no clear evidence showing obvious cultural differences (attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours) in terms of people’s cultural context at a national level, for example, East and West in comparing the public’s reaction towards ‘mask-wearing’ as discussed above.

Notwithstanding the pessimistic side of cultural changes, there are some quite encouraging findings in a study of a national sample (USA) of 1,117 married individuals by the Kinsey Institute in 2020. In this study, 82% of participants agreed that the Pandemic had made them more committed to their marriage, 85% agreed that it was helping them appreciate their family relationships more, just 21% agreed it was damaging their marriage, and only 16% were thinking of divorce or separation (Kinsey Institute, 2020). It is interesting to view the reactions of different attitudes and beliefs in a quite similar situation, environment, and cultural context. The ideas, behaviours, attitudes, beliefs, and value systems have been changed due to the complex challenges from the changing environment – in this case, the COVID-19 Pandemic, and its derivatives – various stresses (of health, job, education, family, finance, and so on). The marital relationships oriented more towards ‘masculine from feminine’ in the family activities due to more lockdown time at home for men. (Browaeys and Price, 2019)

Reaction to the ‘purpose of Life’ (monetary vs spiritual fulfilment)

The widespread infections and sudden deaths due to COVID-19 have caused many people to rethink the purpose of life. There have been significant changes in consumption patterns, work/leisure balances, and choices between working to live and living to work.

CONCLUSION

Changes, particularly drastic changes at a global scale like COVID-19, impact on all aspects of human life. As part of it, the cultural changes – the way of life – are the combinations of impacts of and reactions to the stress, difficulties, and challenges triggered by the unprecedented COVID-19 and the subsequent safety control measures introduced across the globe. Cultural changes such as perceptions of uncertainty avoidance, power distance, social orientation, orientation of marital relationships, and rethinking of purpose of life that are arising from the external pressures relate to actions such as mask wearing, social distancing, and vaccination. Those resulting from internal pressures relate to actions such as masculine-driven readjustment of marital relationship and rebalancing between work and leisure that are taken by the society and its individuals. As discussed, all these cultural behavioural changes simply reflect the anthropologists’ view that ‘cultures provide solutions to problems of adaptation to the environment’ as proposed by Adler et al. (2011).

It is suggested in this paper that these cultural changes have various determinants in regard to the cultural level (national and individual), cultural group (East and West), and cultural dimensions. It is also believed that a better understanding of the impacts of a changing environment on culture and how culture reacts to the challenges and adapt to the environment (economic, social, and political) will benefit from this study in the field of cross-cultural management.

REFERENCES

Adler, N., Gundersen, A., Cullen, J., and Parboteeah, P. (2011). Cross-cultural management. 1st Edition, Cengage Learning Australia, Victoria.

Bajaj, G., Khandelwal, S., and Budhwar, P, (2021). COVID-19 Pandemic and the Impact of Cross-cultural Differences on Crisis Management: A Conceptual Model of Transcultural Crisis Management. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356441063_COVID19_pandemic_and_the_impact_of_cross-cultural differences on crisis management: A conceptual model of transcultural crisis management. Viewed 23 December 2022.

Baldwin, J., Faulkner, S., and Hecht, M. (2006). A Moving Target: The Illusive Definition of Culture, in J. Baldwin, S. Faulkner, M. Hecht, and S. Lindsley (Eds.), Redefining Culture: Perspectives Across the Disciplines. Lawrence Erlbraum Associations, Publishers, New Jersey.

Browaeys, M. and Price, R. (2019). Understanding Cross-Cultural Management. Fourth Edition, Pearson Education Limited, UK.

Ellyatt, H. (2022). Arguing with your partner over Covid? You’re not alone, with the pandemic straining many relationships. CNBC https://www.cnbc.com/2022/01/21/covid-has-put-pressures-and-strains-on-relationships.html Viewed 28 December 2022 Viewed 28 December 2022.

Fitzsimmons, C. (2022). Divorce applications up as marriages hit the rocks. The Sydney Morning Herald https://www.smh.com.au/national/divorce-20220628-p5axco.html Viewed 28 December 2022.

Kinsey Institute (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Marital Quality. https://blogs.iu.edu/kinseyinstitute/2020/11/20/impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-marital-quality/ Viewed 29 December 2022.

Lee, Y.F., Dharba, S., and Rudsari, S. (2021) Covid and cross-cultural management: is there synergy or discord across West- vs. East-developed and newly industrialized economies? https://journals.academicianstudies.com/jmtpr/article/view/15/15. Viewed 22 December 2022.

Nair, N., Selvaraj, P., and Nambudiri, R. (2022). Culture and COVID-19: Impact of Cross-Cultural Dimensions on Behavioural Response. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8392/2/3/81 Viewed 22 December 2022.

Prasso, S. (2020). China’s divorce spike is a warning to rest of locked-down world. Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/world/asia/china-s-divorce-spike-is-a-warning-to-rest-of-locked-down-world-20200401-p54g05 Viewed 28 December 2022.

Savage, M. (2020). Divorce rates are increasing around the world, and relationship experts warn the pandemic-induced break-up curve may not have peaked yet. BBC https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20201203-why-the-pandemic-is-causing-spikes-in-break-ups-and-divorces. Viewed 28 December 2022.

Sun, F. (2020). Covid-19 toll on marriage: divorce inquiries on the rise as stay-home measures push Hong Kong couples off the edge. South China Morning Post https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3083681/covid-19-toll-marriage-divorce-inquiries-rise Viewed 28 December 2022.

Triandis, H. (2002). Subjective Culture. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=orpc Viewed 26 December 2022.

UNESCO (2001). Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/universal-declaration cultural-diversity? Viewed 22 December 2022.

WHO (2022), https://covid19.who.int/?mapFilter=cases. Viewed 26 December 2022.

William R. (1960). Culture and Society. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4608772/mod_resource/content/1. Viewed 22 December 2022.

BIOGRAPHIES

Richard Xi is Deputy Director of postgraduate studies, an Associate Professor, and a Fellow of the Centre for Scholarship and Research at UBSS. His Australian education experience includes a Diploma of Business (SIT), a Diploma of Interpretation (NSIT), a Graduate Certificate in China Studies (USYD), a Graduate Certificate in Business Administration (UBSS), and a Master of Arts in Asian Studies (UNSW). He has been a chief speaker in WSU’s cross-cultural seminar and program and a cultural adviser to two published books.

Gensheng Shen is Vice President (Partnership and Marketing) and Professor at King’s Own Institute (KOI). He has a Bachelor of English Language and Literature from Peking University, a Graduate Diploma and Master degree in Economics from La Trobe University, and a PhD in Finance from Federation University. Gensheng served as Deputy Director of the International Office and Senior Lecturer in Economics at Federation University and Dean of the International Office and Professor at Edith Cowan University.