Issue 3 | Article 3

Abstract

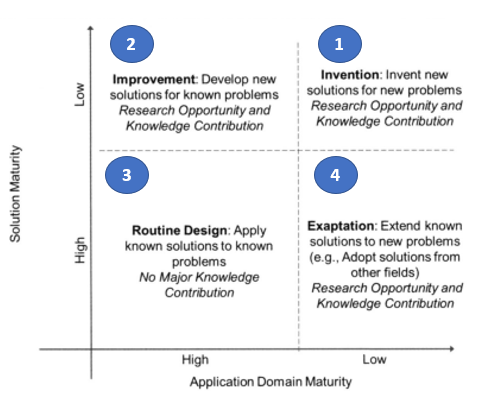

According to Herbert Simon, Nobel Laureate in Economics (1978), the two objectives of a business school are to “train men for the practice of management (or some special branch of management) as a profession, and to develop new knowledge that may be relevant to improving the operation of business” (1967, P.1). However, the traditional model adopted by business schools for achieving these goals is now under siege. This is due partly to one-off events like the COVID-19 pandemic, which has changed the way business operates, and continuing developments such as the proliferation of revolutionary digital technologies, which have changed the way business education is carried out. The authors of this article argue that business schools need to reinvent themselves if they are to future-proof their business models and stay relevant. The challenge they face is great and can only be met if the schools focus on developing new solutions to new business problems rather than extending existing solutions to these problems. They suggest that a framework of design science known as the Domain Maturity-Solution Maturity matrix offers new insights into how business schools can do this.

Business schools: The paradox of purpose

Business schools are educational institutions that specialise in teaching courses and programs related to business and/or management (Kaplan, 2018). In this sense, a business school is also an organisation in which a group of people pursue the common objective of educating others about the business world through coordination ,division of labour, and an integrated information-driven decision making process that takes place continuously through time (Hax & Majluf, 1981). Although business schools have been lauded as success stories of the higher education sector for training millions of MBA graduates (Starkey, Hatchuel, & Tempest, 2004), they have also been criticised for failing to achieve their fundamental goals of relevance and legitimacy (Miles, 2016). Criticisms of the current business school model include the following:

- Business schools produce industry-irrelevant research that is ignored by practitioners such as managers and executives (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002).

- Very few world-changing innovations have originated in business schools or have been shaped by them (Skapinker, 2008).

- Business schools teach bad theories that destroy good management practices (Ghoshal, 2005).

- Business schools have narrowly focused research specialisations led by professors who are “siloed” both in their thinking and in their delivery of content (Podolny, 2009).

- Faculty members have little interest in the critical problems facing business or in helping to solve real world problems faced by industry practitioners (Bennis & O’Toole, 2005; H. Thomas & Wilson, 2011).

- Business school faculties are populated by academic scholars who have little business experience. Therefore, business school graduates have been educated in the practice of a profession by a cadre of faculty members who are not members of that profession and do not have a strong desire to relate to that profession (Bennis & O’Toole, 2005).

- Business schools may have contributed inadvertently to the emergence of hubris in managers and executives (Sadler-Smith & Cojuharenco, 2021).

- Business schools are not creating public value; rather they strive to be cash cows of the universities (Hogan, Kortt, & Charles, 2021).

- Business schools are not professional schools and can’t make management a true profession because their education style has led to numerous corporate scandals (Üsdiken, Kipping, & Engwall, 2021).

These successes and failures, rhetorical or unrhetorical, have given rise to a paradox of purpose and to some extent legitimacy according to which business schools must reinvent themselves to find their true calling, their purpose, and their proper place in the fabric of higher education (Hogan et al., 2021; Miles, 2016; Sadler-Smith & Cojuharenco, 2021; L. Thomas & Ambrosini, 2021).

Reinventing business schools: A growing list of remedies

Several proposals have been made to help reinvent the traditional business school model. For instance, Alajoutsijärvi, Juusola, and Siltaoja (2015) call for a restructuring of curricula, research objectives, and mission towards stakeholder management, practice, and an orientation favouring the human side of business. Üsdiken et al. (2021) argue that debating whether business schools have lost their way and should return to some idealised past are futile and that future discussions should focus on purpose and power, not profession.

Hoffman (2021) suggests nine remedies: (1) instil an ethos of management as a calling, (2) rebuild the business school on a system of aspirational principles, (3) de-emphasize the core, (4) move beyond simply monetary measures, (5) train stewards of the market, (6) re-examine the purpose of the corporation, (7) discard misguided metrics and models, (8) bring the government back in, and (9) pay proper attention to citizenship. Thomas and Ambrosini (2021) contend that business schools must stop regarding value as an output and, instead, adopt a service-dominant logic (SDL) in which value is co-created in an emergent way through interactions with a wide range of stakeholders. More recently, Friedland and Jain (2022) draw on the concept of moral self-awareness and suggest that business schools must redefine the purpose of business, the meaning of professional success, and the ethos of business education itself.

These remedies, although insightful, tend to overlook the impact of two recent exogenous developments on the purpose of business schools. The global pandemic with its crippling consequences, and the digital revolution with its increasingly destructive forces, pose new challenges for determining the purpose of future business schools. Below, the authors address this gap and add to the stream of research on the reinvention of the business school system by borrowing some ideas from the design thinking domain.

The digital revolution, covid-19, and the promise of design

The digital revolution was preceded by a period of data dictatorship and technological totalitarianism, in which mass surveillance as well as data ownership and privacy dominated the technological landscape (Helbing, 2019). The digital revolution has ushered in a period of data democratisation and a form of digital enlightenment, where people can connect, interact from anywhere through anything, and perform numerous tasks that were not possible earlier (Helbing, 2019). As such, it has changed the way education systems work. The revolution has spawned the development of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), which are open-access online courses that allow for unlimited participation, as well as Small Private Online Courses (SPOCs), interactive virtual classrooms, and comprehensive online management platforms. These and other new technologies have led to the rapid growth and global prevalence of online courses, open universities, and networked societies in which students and instructors are connected and interact freely via social networks (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2016). Business schools have also benefited from this paradigm shift by providing online courses and virtual MBAs as well as by offering their courses to wider markets through open universities (Helbing, 2019; Milovich, 2019).

More importantly, when the outbreak of COVID-19 prompted governments to mandate lockdowns and widespread border closures, the new online technologies enabled business schools to move quickly and effectively from onsite to online delivery. The question now is how these schools can regain their relevance and restore their legitimacy while adapting to the wide spectrum of changes instigated by the digital revolution and the pressure to recover from the pandemic. The authors believe that design thinking may offer insightful ideas to address this question.

Design thinking and the business school’s true calling

Design is the set of instructions, based on knowledge, that produces things that people value and use. It embodies the instruction for making the things. However, design is not the thing (Hevner & Chatterjee, 2010). Design thinking is the logic behind every design. It stems from design science, a problem-solving paradigm that seeks to create artefacts such as new ideas, practices, technical capabilities, services, and products through which problems are solved in more efficient and effective ways (Hevner, March, Park, & Ram, 2004).

Design thinking is an iterative and interactive process where designers (a) look for what is there in some representation of problem-solving concepts/ideas, (b) identify relationships between ideas to solve the problem, and (c) use the identified relationships to inform further and better designs/solutions (Razzouk & Shute, 2012). The design cycle accepts that no artefact is perfect. When a design artefact is created it is evaluated and then feedback from the evaluation triggers creation of another artefact (Hevner, 2007). Designers develop and employ various conceptual frameworks that show them betters ways of knowing, framing problems, and designing artefacts (Antunes, Thuan, & Johnstone, 2021). The authors of this article argue that the problem of business school relevance and legitimacy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the advent of the digital revolution can be addressed by changing the way people think about the problem and frame alternative solutions to it. There is no perfect business school; neither is there any perfect curriculum or course design. Design thinking implies that we need to constantly improve what the value or true calling of a business school should be. A conceptual framework in the design science known as the Domain Maturity-Solution Maturity matrix (hereafter DM-SM) as illustrated in Figure 1 (Gregor & Hevner, 2013) can help us achieve this goal.

Figure 1: Domain Maturity-Solution Maturity Matrix (adopted from Gregor and Hevner 2013)

The x-axis represents the maturity of the problem - from high to low. The y-axis represents the maturity of the current artefact that exists as a potential starting point for finding answers to the research question – also from high to low. The four quadrants are:

- Invention, which refers to a new solution applied to a new domain. It denotes a clear departure from the existing and previously established ways of thinking, designing, and doing things. The result is an artefact that can be applied to real world, complex problems. The main starting point in this sphere is a creative and interesting conceptualisation of the problem (Gregor & Hevner, 2013).

- Improvement, which is about devising new solutions to existing problems. The objective here is to design better solutions in the form of artefacts with increased efficiency and effectiveness such as optimized products, extended services, or bundled programs. An improved design is then judged, first, on its ability to clearly demonstrate its way of increasing efficiency and effectiveness, and then on its justification of the reasoning behind the adopted approach (Gregor & Hevner, 2013).

- Routine design, which refers to the application of known solutions to known problems. When there is a known opportunity that can be exploited by applying a known solution, routine design is the best choice. It has been well documented that routine design may lead to serendipitous discoveries (Gregor & Hevner, 2013).

- Expatiation, which is the process of applying an existing design to a new domain or a new problem. Often, designers use artefacts developed in a specific field to solve a problem in a different discipline or domain. For instance, technologies developed by the military are applied in civilian contexts, or frameworks developed in psychology or medicine are applied in economics and business. In expatiation, designers need to demonstrate that extension of the known design to a new problem domain has technical merit, is interesting, and is not trivial (Gregor & Hevner, 2013).

In the next section the authors discuss how using the DM-SM matrix framework can help researchers develop new and better ways to design future business schools.

Designing future business schools: Insights from the DM-SM matrix

It was noted earlier that future business schools will be characterised as high-tech educational institutions that use revolutionary digital technologies and numerous advanced teaching and learning platforms to train students either online or in physical classrooms who can be absorbed into future job markets where technology and socio-environmental responsibilities define strategies. In addition, the pressure to recover quickly from the recent global pandemic and the need for business graduates who can manage future pandemics necessitate a new approach to business education.

The design of future business schools is riddled with complex challenges and technological as well as environmental uncertainties. Thus, the problem is nascent rather than mature. Furthermore, the anecdotal and research evidence briefly reviewed above demonstrate the ineffectiveness of existing approaches to business education.

The authors argue that the design of future business schools will need inventive design thinking (Quadrant 1 of the DM-SM matrix). They believe that future business schools must focus on inventing novel solutions to new business problems rather than on extending existing solutions to new problems. More impactful courses that incorporate technology-driven approaches to social and environmental responsibilities, offering more subjects delivered in different modes, collaborating with a broader range of stakeholders, and focusing on the practical relevance of subjects rather than their theoretical rigour, are just some of the new approaches that can be applied in this emerging domain.

Concluding remarks

Business schools are key players in today’s global higher education system. Regardless of the criticisms that have been levelled at them and the proliferation of demands that they be shut down (Parker, 2018), business schools play a critical role in training the managers of the future. To restore their reputation in the fabric of higher education, business schools need to revisit their design and identify their true calling. The design thinking and in particular the DM-SM matrix suggest that business schools need to develop breakthrough methodologies and solutions that address the new problems that the business world is facing. By doing so, they can reinvent themselves in a meaningful way. The ideas presented in this paper represent an early step on a long and uncharted path. The authors acknowledge that the problem is more complex and the solution more elusive than they have described in this short article. That said, their arguments should provoke new thinking from a different perspective and prompt more research using new methods and designs in this stream.

References

Alajoutsijärvi, K., Juusola, K., & Siltaoja, M. (2015). The legitimacy paradox of business schools: losing by gaining? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(2), 277-291.

Antunes, P., Thuan, N. H., & Johnstone, D. (2021). Nature and Purpose of Conceptual Frameworks in Design Science. Scandinavian journal of information systems, 33(2), 59-96.

Bennis, W. G., & O’Toole, J. (2005). How business schools lost their way. Harvard Business Review, 83(5), 96–104.

Friedland, J., & Jain, T. (2022). Reframing the purpose of business education: Crowding-in a culture of moral self-awareness. Journal of Management Inquiry, 31(1), 15-29.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4(1), 75–91.

Gregor, S., & Hevner, A. R. (2013). Positioning and presenting design science research for maximum impact. MIS quarterly, , 37(2), 337-355.

Hax, A. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1981). Feature Article—Organizational Design: A Survey and an Approach. Operations Research, 29(3), 417-447. doi:10.1287/opre.29.3.417

Helbing, D. (Ed.) (2019). Towards Digital Enlightenment Essays on the Dark and Light Sides of the Digital Revolution. Zürich, Switzerland: Springer.

Hevner, A., & Chatterjee, S. (Eds.). (2010). Design Research in Information Systems: Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Springer.

Hevner, A. R. (2007). A three cycle view of design science research. Scandinavian journal of information systems, 19(2), 4., 19(2), 87-92.

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004). Design science in information systems research. MIS quarterly, 28(1), 75-105.

Hoffman, A. J. (2021). Business education as if people and the planet really matter. Strategic Organization, 19(3), 513-525.

Hogan, O., Kortt, M. A., & Charles, M. B. (2021). Mission impossible? Are Australian business schools creating public value? International Journal of Public Administration, 44(4), 280-289.

Kaplan, A. (2018). A school is “a building that has four walls… with tomorrow inside”: Toward the reinvention of the business school. Business Horizons, 61(4), 599-608.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2016). Higher education and the digital revolution: About MOOCs, SPOCs, social media, and the Cookie Monster. Business Horizons, 59(4), 441-450.

Miles, E. W. (2016). The Past, Present, and Future of the Business School. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Milovich, M. (2019). From Technology Revolution to Digital Revolution: An Interview with F. Warren McFarlan from the Harvard Business School. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 44(1), 152-167.

Parker, M. (2018). Shut Down the Business School: What’s Wrong with Management Education. London, UK: Pluto Press.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. (2002). The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1, 78–95.

Podolny, J. M. (2009). The buck stops (and starts) at business school. Harvard Business Review, 87(6), 62–67.

Razzouk, R., & Shute, V. (2012). What Is Design Thinking and Why Is It Important? Review of Educational Research, 82(3), 330-348

Sadler-Smith, E., & Cojuharenco, I. (2021). Business schools and hubris: Cause or cure? Academy of Management Learning & Education, 20(2), 270-289.

Skapinker, M. (2008). Why business ignores the business schools. Financial Times, January 8.

Starkey, K., Hatchuel, A., & Tempest, S. (2004). Rethinking the business school. Journal of Management Studies, 41(8), 1521-1531.

Thomas, H., & Wilson, A. D. (2011). Physics envy’, cognitive legitimacy or practical relevance: Dilemmas in the evolution of management research in the UK. British Journal of Managemen, 22(3), 443–456.

Thomas, L., & Ambrosini, V. (2021). The future role of the business school: a value cocreation perspective. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 20(2), 249-269.

Üsdiken, B., Kipping, M., & Engwall, L. (2021). Professional school obsession: An enduring yet shifting rhetoric by US business schools. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 20(3), 442-458.

BIOGRAPHIES

Dr Arash Najmaei holds a PhD in strategic management and entrepreneurship from Macquarie University. He is currently working as an associate director of analytics and teaching at various universities. His teaching interests include business research methods, strategic management, entrepreneurship, organizational change, and media management. Dr Najmaei’s research has been published in several journals and research books and presented at international conferences. He has also received three best-paper awards for his research in entrepreneurship and research methods.

Dr Zahra Sadeghinejad graduated with a PhD in management from Macquarie University. She is an active researcher and an award-winning lecturer. Her areas of teaching expertise include marketing, media management, entrepreneurship, and quantitative methods. Dr Sadeghi’s research has been published as book chapters and journal articles and has been presented at prestigious international conferences for which she has received multiple best-paper awards. Dr Sadeghi is currently a lecturer at the Universal Business School Sydney (UBSS), Central Queensland University (CQU), and the International College of Management Sydney (ICMS).

Dr Zahra Sadeghinejad graduated with a PhD in management from Macquarie University. She is an active researcher and an award-winning lecturer. Her areas of teaching expertise include marketing, media management, entrepreneurship, and quantitative methods. Dr Sadeghi’s research has been published as book chapters and journal articles and has been presented at prestigious international conferences for which she has received multiple best-paper awards. Dr Sadeghi is currently a lecturer at the Universal Business School Sydney (UBSS), Central Queensland University (CQU), and the International College of Management Sydney (ICMS).