Issue 2 | Article 14

Abstract

As with many other industries, higher education is filled with Three Letter Acronyms (TLA), such as CRM, SMS, SIS, LMS and FTE. However, Online Program Management (OPM) is not just another TLA. Rather, OPM has the potential to revolutionise higher education design, management, analytics, content standardisation, distribution, and delivery. The theme of this round of the UBSS Publication Series includes updating and enhancing unit content and delivery. Many of the articles address an individual field of study or subject. However, there is a revolution occurring in higher education that will totally change how unit content is developed, the way and by whom it is delivered, the student experience, and the business models that manage these. This article outlines current developments in OPM and presents four scenarios on how OPMs will change higher education during the 2020s.

Introduction

There is a revolution occurring in education right now. It is happening on our higher education campuses, in our homes and workplaces, and in cyberspace. It is the normalisation of online learning and its derivatives – hybrid learning and blended learning.

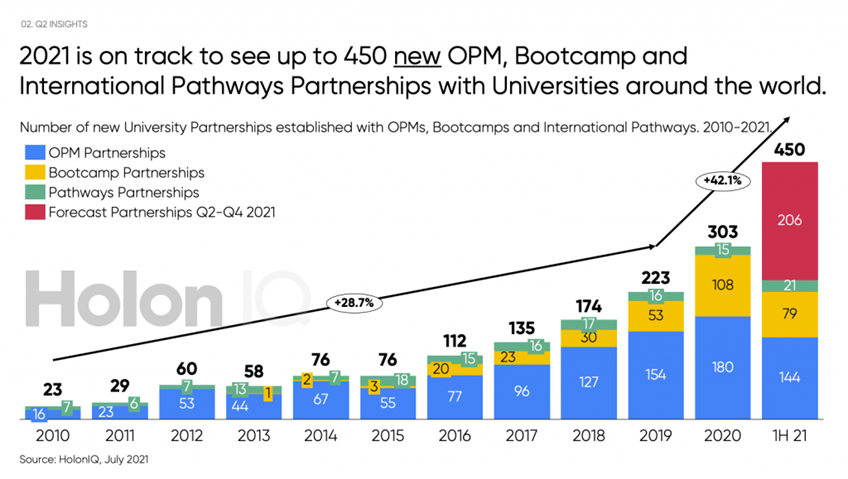

With the acceptance and growth of online, hybrid, and blended learning, higher education providers are looking for greater scale, capability, and flexibility in catering to rapidly changing education markets. OPM providers are helping universities achieve these goals by building, recruiting students for, and distributing their online programs. The global OPM market, which was valued at US$3.9bn in 2020, is projected to reach US$7.7bn in 2025 (HolonIQ, 2021). In the United States, there were over 60 global OPM providers at the end of 2020, and an additional 450 partnership agreements were signed in the first 6 months of 2021. All 40 Australian universities either have an OPM partner or are looking to establish a partnership by 2022.

Impact of COVID-19 on delivery modes

Professor Stephen Parker, former Vice Chancellor of the University of Canberra, observed that the traditional university “is closed and does everything itself. It’s a closed and integrated organisation. And the idea of being a community runs deep. But there are many forces at work now, which make the model hard to maintain. It is inefficient to hold all of that capability in house when you’re not using it all the time” (Hair, 2021).

COVID-19 has become the great accelerator of many social and technological trends. The normalisation of online delivery and its increasing acceptance by higher-education students is one of those trends. It is challenging universities to move away from their traditional, closed model. Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, universities were forced to move all subjects online within weeks. They achieved this through bespoke applications at a subject-by-subject level. The result is a highly varied learning experience for students based on the ability of each lecturer to transform their traditional learning material into online format and deliver it to students using diverse channels of communication.

COVID-19 has accelerated the emergence of a new normal, involving students learning both remotely and face-to-face. Increasingly, students accept online learning, either stand-alone or as part of a blended offering. At UBSS, student feedback surveys (SFUs) conducted over the last four semesters have returned a 90% or higher preference for online learning. Qualitative responses include short-term themes of COVID impact and safety, and longer-term themes of convenience, time and money saved from reduced travel, lower cost of living by relocating away from Sydney to the regions and caring for family.

Pre-COVID-19, the twin successes of Australian universities of (1) progressively moving up the world research rankings and (2) becoming the No. 2 destination for international students, only behind the United States, were interlinked. To fund the research and expand their infrastructure, the universities relied heavily on revenue from the international student market, which peaked in 2019 when 440, 667 international students provided fee revenue of AU$37.6 billion (27.3% of the total revenue of Australian universities) (APH, 2021).

With the subsequent decline in onshore international students and no substantial increase in funding from the Federal Government, the higher education sector faces the problem of delivering online modes efficiently and at scale while maintaining quality teaching and learning. Outsourcing to OPMs may be, at least in part, an effective solution.

Genesis of OPMs

OPMs are a 21st century phenomenon. Academic Partnerships was founded in 2007 and was quickly followed by 2U (whose partners include Harvard and Johns Hopkins Universities) in 2008. The total number of OPMs increased to more than 60 in 2020.

Gartner (2021) defines OPMs as providers that “offer a suite of services either as a package or on a fee-for-service basis. These services include market research, student recruitment and enrolment, course design and technology platforms, student retention, and placement of students in employment or training opportunities.” (Gartner, 2021).

OPMs provide services and support over the whole student life cycle, from initial inquiry all the way to internships and employment services. They are more than just Learning Management Systems (LMS) such as Moodle, Blackboard, and Canvas. They are also more than Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs) such as Coursera and Edx. OPMs aim to use the brand and reputation of the universities and provide a complete suite of services, including instructional design and even course content in the online environment.

Students at universities that use an OPM are generally not aware that they are studying via an outsourced third-party provider. They assume that the lecturers and tutors are the same as those teaching on-campus. Universities do not mention that private companies are helping them run their online degrees. The private third party usually takes 60% of the tuition fees. This is due to the large marketing budgets and fat profit margins of online delivery, where after the initial development costs are covered, the variable cost of delivery is very low, but subject tuition fees remain at the same level. 2U’s 43% margin is split evenly between the university and the OPM (Carey, 2019).

Consolidation and growth of the OPM market

To provide the full suite of services, a series of Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) has occurred in the Education Technology industry over the last year. This has seen OPMs acquiring LMS platforms and MOOCs, providing both parties with a wider range of services.

The size of the global OPM market stands at $3b+ with 60+ OPMs worldwide. An increasing acceptance of online learning sees more universities launching online degrees, with the OPM market expected to reach $7.7b by 2025. Both growth and M&A have accelerated during 2021. They include the 2U acquisition of edX, Keypath Education’s initial public offering (IPO), Noodle acquiring Hotchalk, Zovio expanding its services to become an OPM, the merger of Anthology and Blackboard, and Moodle’s acquisition of three companies (Hill, 2021). 2U’s recent acquisitions indicate how a suite of offerings can be assembled under the one umbrella, with Get Smarter (Short Courses), Trilogy (Bootcamps) and EdX (MOOC) all purchased recently to enable higher education and workforce up-skilling to be provided together.

It is estimated that the top 10 OPM’s receive half of global OPM revenue (HolonIQ, 2021). The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (a measure of market concentration) for the global OPM market contains 250 to 350 companies, which suggests that the market is competitive. It is one of the least concentrated of the global technology markets, indicating there is room for further mergers and acquisitions for consolidation at the top end of the market.

The impact of OPMs on content and delivery

The traditional model of the design, development, and delivery of university content assumes that all activities are conducted in-house. Within a particular faculty, courses are designed based on desired graduate attributes and course outcomes. They are developed by the internal university lecturer or unit co-ordinator, usually based on an external text from a world-renowned subject matter expert. “Universities must have clear course architectures underpinned by pan-university strategies for designing courses, developing content and delivering teaching and learning” (Orton and Curry-Hyde, 2021). The traditional model is based on highly fragmented silos of knowledge within the university which rely on insourcing for the design and delivery of learning materials, as well as student services.

As noted earlier in this article, OPMs are external global organisations offering a full range of software solutions across the whole student experience. The students are often unaware that an external organisation has designed and delivered the learning material, assuming it was all provided by the university. The opportunity for cross-university delivery is particularly the case for professional and technically based degrees such as engineering, information technology, nursing, accounting, and teaching. Due to a state or nationally based professional body accrediting the qualification, this provides national standards of proficiency and expertise in a particular field to deliver the skills, knowledge and attributes required of that profession. This is especially so at the undergraduate level. The question this raises is - if there is a national standard and recommended course materials are provided by national professional bodies, why are these not developed, design and delivered at a national level across all higher education providers?

OPMs may be the answer to this question, with their ability to develop programs at scale and distribute these through the universities and other higher education providers, relying on the universities’ brands for recognition, facilities, and the teacher-related and ancillary services expected from higher education providers. However, this is not a straight-forward development, with many economic, political, and social interests impacting the outcome. Who will design, develop, and deliver the learning material and who will keep the revenue generated from this process are questions that cannot yet be answered with any degree of certainty.

The two main drivers of these scenarios are (1) the probability of further consolidation of the higher education services industry, from what is currently a quite fragmented base, and (2) the forces of outsourcing against the continued insourcing of specialised material. Set out below are four possible scenarios through to the end of this decade that have been proposed by the education technology consultancy HolonIQ (2021).

1) Consolidation/Outsource. This scenario sees the growth and consolidation of global players in the OPM market as providing a wider range of remotely delivered student services, online teaching, and other learning services. As in many of the other global technology markets, oligopolies with great market power form to dominate their markets. This is the natural result of the maturity of OPMs, with a consolidation of industry standards and professional bodies. A few OPMs with a complete range of service offerings dominate, with smaller niche providers forming from opportunities of social change and new technology. Universities have input into the content, but focus more on research and industry partnerships, while handing over the delivery of learning material to OPMs. These OPMs will in turn become targets of the global giant technology companies, as they offer access to the billions of global students.

2) Fragmentation/Outsource. OPMs grow, but new players continue to enter the market. Universities maintain control of the design and development of learning material as well as student services. They do not commit to the complete suite of bundled options from the OPMs. This maintains the competition for OPMs with many providing fee-for-service and commoditised offerings. The success of this scenario is reliant on the universities resourcing and building the key capabilities of course content, which is likely, but less likely is online instructional design, cloud-based technologies, and student user experience required.

3) Consolidation/Insource. Universities co-ordinate their online offerings including student services in a pan-university network. This would be a centralised public alternative to the private OPMs. The higher education providers create a networked approach, relying less on OPMs and more on their intra-university collaboration based on commonalities, such as regional or professional disciplines. Given the continuing competition between universities in Australia and their inability to move beyond their own silo offerings to attract students, this scenario has a low probability of being realised. Similar to scenario 2, it requires resourcing and capability development, as well as collaboration.

4) Insource/Fragmentation. Universities build their own in-house capabilities at the scale and quality of the private OPMs. The universities to retain and reverse the current trend of qualified staff leaving to be employed in private OPMs, taking their knowledge and skill base with them. This scenario requires a strategic re-alignment by universities away from buildings and capital works to investments in online, cloud-based infrastructure and staff development to be able to compete with the global power of the OPMs. It is most likely to be realised among specialised and niche higher education providers with a small student cohort and a strong focus on research and development.

Conclusion

Whatever happens in Australia is small fry compared to the movements in the United States. Just as the FAANGs of US technology impact on all industries, it is the OPMs from the States that have the resources, scale, and attractive business models for the existing high education sector. The Australian edtech players are minnows compared to the great blue whales of the OPMs, which move relentlessly through the global oceans of the higher education sector. The recent impact of COVID in accelerating the uptake of technology, the social change of normalisation of online learning, and the decrease in revenue for Australian universities through closed borders to international students have heightened the likelihood that influence of global OPMs in Australian high education will increase substantially in the coming decade.

References

APH (2021). Overseas students in Australian higher education: a quick guide Updated 22 April 2021. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp2021/Quick_Guides/OverseasStudents , viewed 25th September, 2021.

Carey, K (2019). The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education. Huffpost, https://www.huffpost.com/highline/article/capitalist-takeover-college/ , viewed 20th September 2021.

Gartner (2021). Online Program Management in Higher Education.

https://www.gartner.com/reviews/market/online-program-management-in-higher-education , viewed 26th September 2021.

Hare, J (2021). Online Boom Ahead as Unis Outsource Teaching. Australian Financial Review, 24 May 2021 edition.

Hill, P (2021). OPM Market Landscape and Dynamics Summer 2021 Updates.

https://philonedtech.com/opm-market-landscape-and-dynamics-summer-2021-updates/ , viewed 25 September 2021.

HolonIQ (2021). 244 University Partnerships in the First Half of 2021.

https://www.holoniq.com/notes/opm-mooc-opx.-244-university-partnerships-in-the-first-half-of-2021/ , Viewed 24 September 2021.

Orton, T and Curry-Hyde, E (2021), Our Universities Have Been Gold Medallists Before, Here’s How they can do it again – Nous Group. https://www.nousgroup.com/insights/universities-gold-medallists/, viewed 2nd October, 2021.

Biography

Professor Andrew West is Dean of the Universal Business School Sydney (UBSS) and Provost of the Blended Campus. Formerly, he was Director of the Centre for Entrepreneurship at UBSS. Andrew has worked in academia for 14 years, following a successful 10-year career an entrepreneur and business owner/manager. His research output includes 12 peer-reviewed journal articles and numerous conference papers. Andrew’s main research areas are marketing and higher education.