Issue 2 | Article 9

Abstract

Knowledge and intellectual capital are key resources driving the knowledge economy. Organisations are seeking to gain a competitive advantage and improve their business performance by increasing their knowledge and enhancing their intellectual capabilities in an ever-changing business environment. However, how to effectively utilise and leverage knowledge and intellectual capital to maximise organisational value is a constant challenge for management. This article reviews and discusses the dimensions of intellectual capital, the key components of the knowledge management system, the dynamic interactions among these, and the roles they play in creating value within organisations.

Introduction

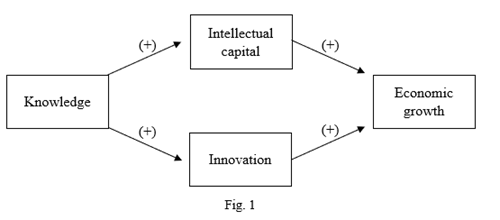

With the transition from the Industrial era (1800-2000) to the Digital era (from 2000), economies are moving away from heavy dependence on physical assets such as natural resources, labour, and machinery towards greater reliance on intangible assets such as knowledge and intellectual capital (Powell & Snellman, 2004; OECD, 2005). Knowledge is the most important business resource in a knowledge-based economy (Drucker, 1993). The key components of the knowledge economy – intellectual capital and innovation - are both tied to and originate from knowledge. They are the key mediating variables between knowledge (the independent variable) and economic growth (the dependent variable) (see Fig. 1 below). They allow companies to gain a competitive advantage, thereby increasing revenue, containing costs, and creating organisational value. Business leaders “seek to shape and position the organisation’s assets, driving forces and activities to remain competitive” (Wiig, 1997, p 399). The ability of companies to gain competitive advantage and create value is determined mainly by their ability to manage knowledge.

Intellectual capital and its three dimensions

Intellectual capital

There is no agreed definition of intellectual capital (IC) among academics. Stewart (1997) considered it to be intellectual material - such as knowledge, information, intellectual property, and experience - that can be used to create wealth. Investopedia (2021) defined it as the value of the organisation’s employee knowledge, skills, business training, and proprietary information that provide it with a competitive advantage. Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) referred to it as “the knowledge and knowing capability of a social collectivity, such as an organisation, intellectual community, or professional practice’ Focusing on the organization itself, Edvinsson and Malone (1997) defined IC as the sum of human and structural capital, which together encompass the applied experience, organisational technology, customer relationships, and professional skills that provide a company with a competitive advantage in the marketplace. However, while not identical, these views on IC have some common elements including information, knowledge, and collective knowing capability. IC enables organisations to gain competitive advantage, improve business performance, and create company value. It does this by enhancing business activities such as strategy formulation, innovation, technical development, and management.

Edvinsson (1997), developer of the Scandia model, started with the proposition that the value of a company is ultimately determined by the market. However, the market value of a company is normally greater than the book value (the sum of all the measurable, net tangible assets of the company) as determined by the application of traditional accounting methods. This difference represents the company’s IC (Dalkir, 2017). It is a ‘hidden’ asset, having no monetary presence on the financial statements and reports that have been prepared by the company. However, it truly exists as part of the company’s assets and this monetary value is recognised by the market. Developing this ‘hidden value’ is an important challenge for organisations seeking to create wealth.

The three dimensions of IC and the value creation link

It is common practice to divide an organisation’s IC into three categories (or dimensions): human capital (HC), organisational (or structural) capital (OC), and relational (or customer) capital (RC) (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Marr, 2008; IFAC in CIMA n.d. P.7). As described by Edvinsson (1997):

- HC covers mostly people’s knowledge and skills, know-how, work-related experience, competencies, creativity, and entrepreneurial spirit.

- OC encompasses mainly corporate culture and management philosophy, organisational processes, information systems, trade secrets, trademarks, patents, and copyrights.

- RC includes the organisation’s formal and informal relationships (internal and external), customer loyalty and engagement, distribution channels, brand names, corporate reputation, business collaborations, and licensing agreements.

HC is embedded in people’s minds. It is the knowledge (most of which is tacit, such as personal know-how, insights, understandings, and experiences) and skills the employee uses to perform their tasks individually or collectively to achieve the organisation’s goals. It can be gained from formal/informal education/training and/or accumulated from working, learning, and social experiences. Knowledge is at the centre of the IC platform. It is a key resource in managing the company’s routine business activities. It also plays an important role in developing creativity, innovation, and an entrepreneurial spirit, all of which are vital for organisations seeking to gain a competitive edge, create value and generate wealth in a changing business environment.

OC refers to the structure, systems, and culture of an organisation. From Marr’s (2008) viewpoint, OC includes the organisation’s corporate values and management philosophy, its processes and routines, and its intellectual property (e.g., patents, copyrights, and trademarks). Edvinsson and Malone (1997) described structural capital as what remains in the organisation after all the people are removed. It includes the company’s process capital and innovation capital. OC determines the quantity and quality of the HC (such as know-how and skills) used in performing the routine tasks of the organisation. However, OC can also foster another critical aspect of knowledge – people’s attitudes – by developing and nurturing a cultural environment that promotes creativity and innovation. An organisation’s innovation capital is a component of OC (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997). It is initiated by people’s new and creative ideas based on their knowledge, experience, intuition, attitude, and other knowing-ability (HC elements) and is facilitated and institutionalised by corporate culture and management philosophy (OC elements). The relationships (connections, interactions, and influence) between HC and OC are particularly important in the process of creating organisational value through innovation.

RC comprises all the internal and external relationships that an organisation holds with its customers. It includes customer loyalty, brand images, business collaborations, distribution channels, and social networks. It is the final component in the IC value creation chain, ensuring that the company’s products and services satisfy customers’ needs, and therefore create value for the company. Value creation cannot occur in the absence of effective and efficient RC and its successful integration with HC and OC. Consequently, RC plays a pivotal role in the process of translating IC into market value.

Knowledge and knowledge management

“We now know that the source of wealth is something specifically human: knowledge. If we apply knowledge to tasks we already know how to do, we call it “productivity.” If we apply knowledge to tasks that are new and different, we call it “innovation.” Only knowledge allows us to achieve those two goals.” (Drucker 2000, p. 96)

The knowledge management concept

Since knowledge is the driving force of economic growth and wealth creation, its acquisition and exploitation have become important objectives for organizations striving to achieve sustainable competitive advantage and business success. Hence, the ability to manage knowledge has become crucial in today’s knowledge economy (Dalkir, 2017). With knowledge management (KM) developing into a cross-disciplinary field - ranging from anthropology, management science, information technology, and organizational behaviour to cognitive science and sociology - there is currently no consensus on its definition. Jashapara (2011, p.14) defined it as “the effective learning processes associated with exploration, exploitation and sharing of human knowledge (tacit and explicit) that use appropriate technology and cultural environments to enhance an organisation’s intellectual capital and performance.” From a business management perspective, KM can considered as either an organisational strategy or a systematic process for leveraging knowledge to gain a competitive edge and increase organisational value.

However, it is not sufficient just to possess knowledge. As Dalkir (2017, p.2) points out, “Knowledge is abundant, but the ability to use it is scarce.” Efficient and effective KM can lift business performance and act as a catalyst for the innovation of new products and services, which is a key to business prosperity and sustainability (Liu, 2020). The argument that ‘If knowledge is power, then KM must be even more powerful’ reflects the intrinsic value of KM. The latter converts knowledge into power and uses this power to create economic and business value.

The knowledge management process and the value creation link

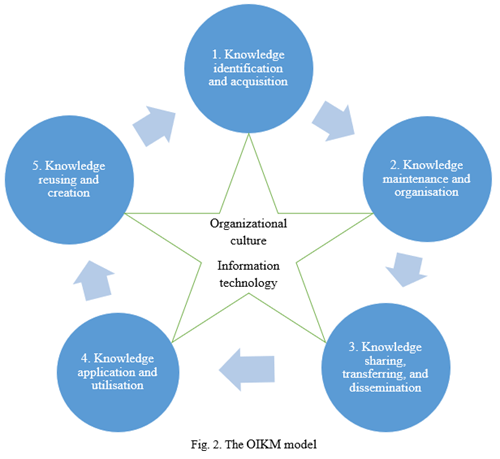

Notwithstanding that there are various KM process models, developed from different perspectives (e.g., different industries and different types of business), the KM process should be considered, from a holistic view, as an open, integrated system that incorporates key environmental elements (corporate culture and information technology). (See Fig. 2: The open integrated KM model (OIKM).

The KM model has five stages. Since the activities in each stage interact with and are influenced by activities in other stages, the effectiveness of the process and the quality of the outputs at each stage are crucial to the effectiveness and quality of the output at succeeding stages. For example, the quality of output from Stage 1, ‘Knowledge identification and acquisition’ should be the ‘right’ knowledge before it enters Stage 2, ‘Knowledge maintenance and organisation’. In turn, this correct knowledge should be maintained and organised properly so that it can provide the most value when it enters Stage 3, ‘Knowledge sharing, transferring, and dissemination’ – i.e., giving the right knowledge to the right person, in the right place, and at the right time. Further, the success of value creation from the KM processes is also significantly impacted by the synergy among these processes. Finally, whether taking the KM system as a whole or viewing KM as a set of processes, the overall outcome is greatly shaped by the KM environment, particularly the organisational culture, and information technology.

The first stage in the KM process comprises identifying what knowledge the organisation needs (the right knowledge), seeking that knowledge (knowledge exploitation and exploration), and acquiring the knowledge (from either inside of and/or outside of the organisation). The second stage, - maintaining and organising knowledge - covers the processes of analysing, classifying, and storing the gained knowledge (where the dimensions of knowledge include marketing knowledge, management knowledge, and financial knowledge), generally with the support of information technology. Then, the knowledge is ready to go to the third stage – that of sharing, transferring, and disseminating. While explicit knowledge (mainly documents) can be easily articulated, shared, and disseminated, doing so is more complicated and challenging for tacit knowledge (which resides in people’s minds). However, tacit knowledge (e.g., know-how, understanding, intuition, attitude, and experience) is the more valuable component of HC. Acquiring, sharing, and disseminating tacit knowledge requires its own set of specific knowledge and skills, and it is a continuing challenge for organisations to acquire, maintain, and develop these. The fourth stage is the application and utilisation of knowledge to realise value for the organisation. In the fifth and final stage, all inputs, processes, and outputs from the four earlier stages are assessed, leading to knowledge reusing (for best practices) and creation (lessons learned, new ideas and new ways of doing things occur, and innovations on the horizon).

Conclusion

Knowledge and intellectual capital (IC) are key resources for organisations seeking to obtain a competitive advantage in order to create value and generate wealth in the knowledge economy. However, the conversion of knowledge into real ‘power’ (ability to create value) and sustaining a profitable return from IC are complicated and challenging tasks for organisations. Having examined and reviewed the key elements of the IC with their subtle relationships embedded in the fabric of HC, OC, and RC, and worked through the processes of the KM system with their dynamic interactions between components and stages, it is suggested that important value-creation links do exist between knowledge, IC and KM and among the elements and components of IC and KM. Achieving the organisational goal of value creation is determined not only by the amount of IC and knowledge, but also by the intellectual capability of the organisation to manage this knowledge.

References

CIMA (n.d.). Understanding corporate value: managing and reporting intellectual capital. https://www.cimaglobal.com/Documents/ImportedDocuments/intellectualcapital.pdf viewed 10 September.

Dalkir, K. (2017). Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice. 3rd Edition, The MIT Press, London.

Drucker P.F. (1993). Post Capitalist Society. http://pinguet.free.fr/drucker93.pdf viewed 4 September 2021.

Drucker P. F. (2000). The Ecological Vision, Reflections on the American Condition. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick and London.

Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. S. (1997). Intellectual Capital: Realizing Your Company’s True Value by Finding its Hidden Brainpower. Judy Piatkus (Publishers) Ltd, London.

Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/i/intellectual_capital.asp viewed 2 September 2021.

Jashapara A. (2011), Knowledge Management an Integrates Approach. 2nd Edition, Pearson Education Limited, England.

Liu S. (2020). Knowledge Management: An interdisciplinary approach for business decisions. Kogan Page Limited, London.

Marr B. (2008). Impacting Future Value: How to Manage Your Intellectual Capital https://www.cimaglobal.com/Documents/ImportedDocuments/tech_mag_impactingfuturevalue_may08.pdf.pdf viewed 2 September 2021

Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S. (1998), Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 242-266.

OECD (2005), Knowledge-based Economy. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=6864 viewed 4 September 2021.

Powell W. and Snellman K. (2004). The Knowledge Economy https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234838566_The_Knowledge_Economy viewed 4 September 2021.

Stewart, T. A. (1997), Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations. Doubleday/Currency, New York.

Wiig K. M. (1997) Integrating Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Management. Long Range Planning, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 399-405.

Biography

Richard Xi is a Senior Postgraduate Coordinator and an Assistant Professor at UBSS. His Australian education qualifications include a Diploma of Business (SIT), a Diploma of Interpretation (NSIT), a Graduate Certificate in China Studies (USYD), a Graduate Certificate in Business Administration (UBSS), and a Master of Arts in Asian Studies (UNSW). He has been a Principal Speaker in WSU’s cross-cultural seminar program and a Cultural Adviser for two published books.