Issue 3 | Article 4

Abstract

Teaching is not synonymous with learning. If the flip side of teaching was learning, then teaching would be easy. However, learning is a multi-faceted activity, and many variables are at play. It is also an individual journey, and if teaching is to promote effective learning, it must align with the personal strengths of each student. Models and theories that are learner-focused and recognise this alignment, such as Multiple Intelligences (MI) theory, would yield better learning outcomes. This article invites all teachers to consider using these learner-focused tools in online delivery.

Introduction

It is premature to conclude that the days of in-class, face-to-face teaching and learning are over. Nevertheless, around the globe and from elementary to tertiary level, online learning and teaching (L&T) is now the most popular form of delivery. It is imperative, therefore, to make online education as interesting and effective as possible.

The growth of online learning

Irresistible globalisation, the favourable value judgments attached to foreign degrees, the lure of living and settling in a country of one’s choice, the advancement of information and communication technology (ICT), and the digitalisation of the economy have contributed to the rapid growth of online learning (Moessenlechner et al., 2021). The internet, in particular, has changed almost all aspects of human life. Today's students are 'tech savvy' and there are opportunities for them to do many things - if not everything - online.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of online learning. Across the globe, it made it easy for the ‘willing’ and the ‘in-between’, whilst forcing the ‘unwilling’, to abandon traditional fixed-scheduling, synchronous, face-to-face teaching and learning in favour of e-learning on digitalised platforms. ‘Even before COVID-19, education technology (EdTech) investments reached US$ 18.66 billion in 2019 with a projection to reach $ 350 billion by 2025’ (Li & Lalani, 2020, p. 1).

The advantages of online learning and teaching

Online learning started to gain popularity long before the onslaught of COVID-19, and it did so for several reasons. First, online learning provides more flexibility in terms of outreach. Any number of audiences (irrespective of geographical location) can be catered for without proportionate increase in cost and effort, both at the delivery and the recipient ends. Learners have the option of participating from almost anywhere, and mostly without stepping out from their comfort zones (homes). Second, it is cheaper, since the huge accommodation and travel costs associated with face-to-face learning are avoided. If the time required for travel is expressed in monetary terms, then the cost saving is much greater still, since at any given point in pre-COVID-19 times, millions of students were on the move across towns, cities, countries, and continents to attend face-to-face teaching sessions. Third, the incalculable psychological and emotional costs of being away from home, family, and friends to attend onsite, face-to- face sessions are also avoided for many million international students who, otherwise, would have been on the move from their home countries to host countries for this purpose.

Sharing information and remaining in touch are much easier online. With access to the right technology, online learning can be quicker and more effective for retaining information (Li & Lalani, 2020). A mindset that goes beyond the physical classroom-structure based delivery and uses ‘a range of collaboration tools and engagement methods is likely to promote inclusion, personalisation, and intelligence’ in online delivery (Tong, 2020).

The disadvantages of online learning and teaching

Online learning is not devoid of challenges. Reliable internet connection is a requirement for remote learning to be effective. In some European countries, 95% of school students have access to a computer whilst the proportion is only 34% in Indonesia (Li & Lalani 2020). Students do not have uniform styles of learning (Chavan, 2011). Also, online teaching requires that the teacher be able and willing to ‘avail the opportunity of providing differentiated instruction’ for an increasingly diverse student cohort as well as enable learners ‘to play out their personal strengths, skills, and interests’ (Schmitz & Foelsing, 2019). Walker, Rummel & Koedinger (2011) believe that online education requires an atmosphere of ‘support learning’ rather than ‘standardised lecture-based instruction’. This requires careful and concerted effort. The challenges can also be looked at from multiple angles like content, context, delivery, and recipients (Uddin, 2021).

Absence of strong leaders who have a firm conviction in the value of online education and the right mindset at the institutional level is also an important challenge. In some cases, an adequate support system for the academics involved in preparing, presenting, and facilitating the delivery of online materials has not been available. Getting the right balance between face-to-face and online delivery is also a formidable challenge.

The need for a review of online L&T strategies

Given the realities on the ground, a careful crafting and implementation of strategies is an imperative for enhancing the effectiveness of online L&T. Learner engagement is a precondition for institutions remaining relevant and their programs being of value and sustainable. The ‘overnight everything online’ reality following the COVID-mandated lockdowns did not allow time for trialling different methodologies or for debating and deliberating on the merits of different approaches prior to their adoption. However, the dust has not yet settled, so scope for experimentation does still exist.

Online student cohorts represent multifarious backgrounds, each with their in-built strengths and priorities. With teaching being viewed as not merely a delivery system but also a creative profession (Robinson, 2013), programs that celebrate students’ various talents and excite curiosity will be the ultimate winners. Therefore, it is worth examining theories/models that have the potential to form part of an ‘inclusive pedagogy that could better inform learning and teaching in higher education’ (Barrington, 2004) and which are likely to enhance learning experiences. ‘Self-motivation and personal goals’ are also important determinants for choosing among different modes of delivery. So, ‘it is important to understand how individuals self-select to consume content and pursue their goals within these settings’ (Lu, Bradlow & Hutchinson, 2022, p. 35).

If teachers appreciate this and adjust their content and delivery accordingly, learning outcomes will be improved. Learning is never guaranteed, nor can it be taken for granted unless learners’ inherent strengths, styles and intelligences are taken on board. If this paper can rekindle in some teachers the desire to consider multiple intelligences alongside various learning styles of the participants and explore ways of incorporating their findings into online delivery, it will have achieved its purpose. The article is not, therefore, intended to be an end, but rather the beginning of a constructive discourse.

Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory

Recognising the diversity of human intelligence and considering new research undertaken in several cognitive disciplines, Howard Gardner (1983, 1999) developed the Multiple Intelligences (MI) theory. This theory is firmly grounded in the premise that people possess multiple intelligences, and that they process information with these intelligences in ways that are different from, and independent of, each other. The pervasiveness of online L&T makes it important for all teachers to consider theories, models, and strategies that have the potential to add value as well as enhance the sustainability and effectiveness of academic programs. It will not be surprising if, at some stage in the future, the relevance and sustainability of institutional teaching comes under the spotlight in terms of whether learners’ strengths are being considered at the design stage. If educators can allow theories and models (like Gardner’s MI theory) to inform their lessons and delivery, the outcome for online L&T will be bright.

Gardner’s theory was the inspiration for this paper. It has the potential to make a major, positive impact on the quality of higher education. A teacher with a logical mind should not hesitate to give such theories ‘a go’ to see if they help ameliorate some of the current weaknesses in online teaching. Earnie Barrington (2004) was convinced about the relevance and the application of MI (amongst some other learning pedagogies) in higher education. Individuals possess various intelligences in different degrees, some of which could be their unique strength. Thus a ‘one size fits all’ approach to teaching is unlikely to work for all students. According to Gardner (1983, 1999), a strategy that aims at creating an opportunity for participants to capitalise on their strongest intelligences is likely to be the most effective approach. This should accompany student-centred teaching, assessments, and ongoing positive as well as negative but developmental feedbacks.

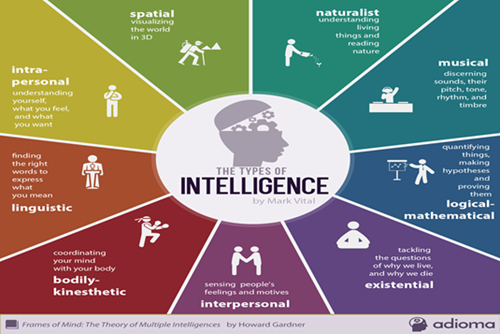

Gardner was convinced that the most effective strategies are those that use instruction and content that provide participants with the opportunity to learn ‘in a way that works best for them’ with the help of the unique intelligences they possess and are comfortable using. He was convinced that ‘anything can be taught in a number of ways’ and that ‘education that treats everyone in the same way is the most unfair education’ (Gardner, 1999). He identified nine different intelligences- originally seven, to which he added the Naturalistic and the Existential - as useful constructs (Appendix-A). Gardner’s original proposition was aimed at school-going students, and it was in the context of face-to-face teaching. However, it is appropriate for all levels of education and for online delivery.

MI theory is based on self-reporting questionnaires (Appendix-B), and it has its fair share of critics. For example, MI intelligences are broad, are not based on or supported by empirical evidence, and rigorous empirical evidence is not yet available to support the theory. Gardner was aware of these criticisms, but he was also convinced of the benefits of MI theory irrespective of its ‘scientific merits’ (Gardner, 1999). As the massive online L&T is still in its formative stage, teachers can afford to experiment now to see if MI does or does not facilitate learning.

At the outset, instructors might use Gardener’s MI questionnaire to identify learners’ strengths in terms of intelligences. This activity might also serve as ‘an eye-opener’ for the learners due to its self-discovery nature. It might not be possible to devise and deliver individually tailored activities for large cohorts of learners based on their various intelligences. Catering for each individual student separately is unrealistic; however, it has never been the intent of MI theory, and it is not being advocated here. Rather the objective proposed is to identify the predominant strengths and learning styles of most students and to incorporate them in content and delivery plans. Less prevalent forms of intelligence must also be taken into consideration so that there is something for everyone. This approach is made feasible by the ‘self-paced’ nature of online learning.

It should also be remembered that, like personality dimensions, every intelligence is present in varying degrees in every individual. Students in business courses must be given content, activities, and assessments that allow them to capitalise on their Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, Linguistic, Logical-Mathematical, and Naturalist intelligences as and when appropriate. Content so devised and delivered enhance the learning process without the learners being consciously aware of the ultimate intent behind them. It is a seamless process. For some non-business courses, opportunities to use Kinaesthetic, Spatial, Musical and Existential intelligences should also be explored. In this context, it is worth remembering that the ‘hands-on’, explorative, experimental, and reflective types of learning are also the most enjoyable.

The Index of Learning Styles (ILS) [Appendix-C] can also be used. Students would benefit from being aware of their individual learning styles as this knowledge has the potential to act as a ‘eureka moment’ for them. Awareness is not a guarantee of effective learning, but the knowledge should help most learners control their learning journey and choose the courses that fit in best with their demeanour.

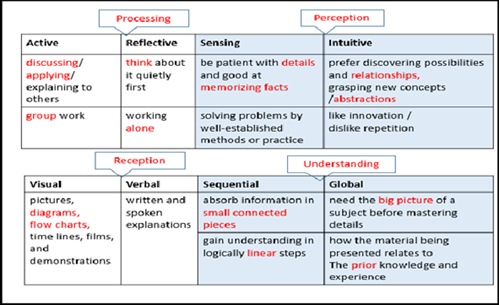

As an example, a learner with a strong preference for reflective rather than active learning would “prefer to think about it quietly first rather than seek to understand it best by doing something active with it. ‘Let’s try it out and see how it works’ is an active learner’s phrase; ‘Let’s think it through first’ is the reflective learner’s response”. Active learners generally prefer to work in groups whereas reflective learners would rather work alone. Not having an opportunity to think or work alone can be frustrating for a reflective learner. There must be scope for sensitive individuals to augment their understanding by learning facts while still accommodating the intuitive student who ‘often prefers to discover possibilities and relationships’. If a person prefers a sequential style - i.e., tends to gain understanding in a sequential fashion, with each step following logically from the previous one, they should not be presented with an approach devised for a global learner (Felder and Soloman, 1993, pp.1-2).

Another aspect that needs careful attention is interactive learning. Online learning removes the 'taken for granted' scope and opportunity for wholesome multi-dimensional real time interaction plus social learning. It is therefore imperative for policy makers, strategists, educators, and facilitators to develop courses that have in-built opportunity and scope for the uses and the interplay of learners’ multiple intelligences and learning styles. It may not be an easy task, but it is an important one. So, let's get on with the job!

References

Barrington, E. (2004). Teaching to student diversity in higher education: how Multiple Intelligence Theory can help. Teaching in Higher Education, 9(4), October. Carfax Publishing- Taylor & Francis Ltd. The University of Auckland, New Zealand, 421-434.

Chavan, M. (2011). Higher Education Students’ Attitudes Towards Experiential Learning in International Business. Journal of Teaching in International Business. 22, 126–143.

Felder, R.M. & Silverman, L. K. (1988). Learning and Teaching Styles in Engineering Education. Engineering Education. 78(7), 674–681.

Felder, R.M. & Soloman, B. A. (1993). Learning Styles and Strategies. USA: North Carolina State University.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of Mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1997). Howard Gardner on multiple intelligences. Edutopia- George Lucas Educational Foundation. Available via https://www.edutopia.org/video/howard-gardner-multiple-intelligences

Gardner, H. (1999) Intelligence Reframed. Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2009). Howard Gardner of the Multiple Intelligence Theory. Edutopia.org., Nov 7. Available via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l2QtSbP4FRg

Gardner, H. (2015). Frames of Mind - Theory of Multiple Intelligences,

Aug 27. Available via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H1J2fzzYWic

Li, C. & Lalani, F. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed education forever. This is how. World Economic Forum. 29 April 2020. Available via https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/ r 2020.

Lu, J., Bradlow, E. T. & Hutchinson, J. W. (2022). Testing Theories of Goal Progress in Online Learning. Journal of Marketing Research. 59(1), 35–60.

Moessenlechner, C., Obexer, R., Pammer, M. & Waldegger, J. (2021).

Switching Gears Online Teaching in Higher Education in the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. iJAC Online Journal, 14(2), pp. 27-43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3991/ijac.v14i2.24085. Management Center Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria.

Schmitz, A. P. and Foelsing, J. (2019). Social Collaborative Learning Environments in Leadership Education in The disruptive power of online education: Challenges, opportunities, responses, A. Altmann, B. Ebersberger, C. Mössenlechner, and D. Wieser, Eds., Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, 99–123.

Robinson, K. S. (2013). How to escape education's Death Valley. TED Talks Education. May 2013. Available via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wX78iKhInsc. Viewed on 23 March 2022.

Tong, D. (2020). Senior Executive Vice President of Tencent and President of its Cloud and Smart Industries Group, cited in Li & Lalani, 2020.

Uddin, S. J. (2021). Enhancing Students’ Engagement? Let’s Get Real! Updating and Enhancing Course Content, Course Delivery, and Academic Management, A. Hooke and G. Whateley, Eds., Universal Business School, Sydney, Vol. 2, 75-84.

Walker, E., Rummel, N., & Koedinger, K. R., (2011). Designing automated adaptive support to improve student helping behaviours in a peer tutoring activity. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 6(2), 279–306. Available via https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-011-9111-2. Retrieved on 10 February 2022.

Appendix A. Multiple intelligences examples

Source: Mark Vital retrieved from https://blog.adioma.com/9-types-of-intelligence-infographic/ on 2 April 2022

Appendix B: Multiple intelligences questionnaire

Howard Gardner’s MI Test Questionnaire can be downloaded for free from ACADEMIA.edu via https://www.academia.edu/35168075/Howard_Gardner_Multiple_Intelligence_-Test.

This questionnaire can also be administered online, and it is available via https://www.literacynet.org/mi/assessment/findyourstrengths.html.

Appendix C: Learning style questionnaire

Please circle either “a" or "b" to indicate preference to every question. All questions must be answered. If both "a” and “b” seem to apply, choose the one that applies more frequently.

- I understand something better after I

(a) try it out.

(b) think it through. - I would rather be considered

(a) realistic.

(b) innovative. - When I think about what I did yesterday, I am most likely to get

(a) a picture.

(b) words. - I tend to

(a) understand details of a subject but may be fuzzy about its overall structure.

(b) understand the overall structure but may be fuzzy about details. - When I am learning something new, it helps me to

(a) talk about it.

(b) think about it. - If I were a teacher, I would rather teach a course

(a) that deals with facts and real-life situations.

(b) that deals with ideas and theories. - I prefer to get new information in

(a) pictures, diagrams, graphs, or maps.

(b) written directions or verbal information. - Once I understand

(a) all the parts, I understand the whole thing.

(b) the whole thing, I see how the parts fit. - In a study group working on difficult material, I am more likely to

(a) jump in and contribute ideas.

(b) sit back and listen. - I find it easier

(a) to learn facts.

(b) to learn concepts. - In a book with lots of pictures and charts, I am likely to

(a) look over the pictures and charts carefully.

(b) focus on the written text. - When I solve math problems

(a) I usually work my way to the solutions one step at a time.

(b) I often just see the solutions but then have to struggle to figure out the steps to get to them. - In classes I have taken

(a) I have usually got to know many of the students.

(b) I have rarely got to know many of the students. - In reading non-fiction, I prefer

(a) something that teaches me new facts or tells me how to do something.

(b) something that gives me new ideas to think about. - I like teachers

(a) who put a lot of diagrams on the board.

(b) who spend a lot of time explaining. - When I'm analyzing a story or a novel

(a) I think of the incidents and try to put them together to figure out the themes.

(b) I just know what the themes are when I finish reading and then I have to go back

and find the incidents that demonstrate them. - When I start a homework problem, I am more likely to

(a) start working on the solution immediately.

(b) try to fully understand the problem first. - I prefer the idea of

(a) certainty.

(b) theory. - I remember best

(a) what I see.

(b) what I hear. - It is more important to me that an instructor

(a) lay out the material in clear sequential steps.

(b) give me an overall picture and relate the material to other subjects. - I prefer to study

(a) in a group.

(b) alone. - I am more likely to be considered

(a) careful about the details of my work.

(b) creative about how to do my work. - When I get directions to a new place, I prefer

(a) a map.

(b) written instructions. - I learn

(a) at a fairly regular pace. If I study hard, I'll "get it."

(b) in fits and starts. I'll be totally confused and then suddenly it all "clicks." - I would rather first

(a) try things out.

(b) think about how I'm going to do it. - When I am reading for enjoyment, I like writers to

(a) clearly say what they mean.

(b) say things in creative, interesting ways. - When I see a diagram or sketch in class, I am most likely to remember

(a) the picture.

(b) what the instructor said about it. - When considering a body of information, I am more likely to

(a) focus on details and miss the big picture.

(b) try to understand the big picture before getting into the details. - I more easily remember

(a) something I have done.

(b) something I have thought a lot about. - When I have to perform a task, I prefer to

(a) master one way of doing it.

(b) come up with new ways of doing it. - When someone is showing me data, I prefer

(a) charts or graphs.

(b) text summarizing the results. - When writing a paper, I am more likely to

(a) work on (think about or write) the beginning of the paper and progress forward.

(b) work on (think about or write) different parts of the paper and then order them. - When I have to work on a group project, I first want to

(a) have a "group brainstorming" where everyone contributes ideas.

(b) brainstorm individually and then come together as a group to compare ideas. - I consider it higher praise to call someone

(a) sensible.

(b) imaginative. - When I meet people at a party, I am more likely to remember

(a) what they looked like.

(b) what they said about themselves. - When I am learning a new subject, I prefer to

(a) stay focused on that subject, learning as much about it as I can.

(b) try to make connections between that subject and related subjects. - I am more likely to be considered

(a) outgoing.

(b) reserved. - I prefer courses that emphasizes

(a) concrete material (facts, data).

(b) abstract material (concepts, theories). - For entertainment, I would rather

(a) watch television.

(b) read a book. - Some teachers start their lectures with an outline of what they will cover. Such

outlines are

(a) somewhat helpful to me.

(b) very helpful to me. - The idea of doing homework in groups, with one grade for the entire group,

(a) appeals to me.

(b) does not appeal to me. - When I am doing long calculations,

(a) I tend to repeat all my steps and check my work carefully.

(b) I find checking my work tiresome and have to force myself to do it. - I tend to picture places I have been

(a) easily and fairly accurately.

(b) with difficulty and without much detail. - When solving problems in a group, I would be more likely to

(a) think of the steps in the solution process.

(b) think of possible consequences or applications of the solution in a wide range of

areas.

After completing the scoring as per authors’ instructions (scoring instructions and interpretations have not been shown here), the person attempting the questionnaire can learn their preferences for learning from the table below:

Source: Jingyun Wang, & T. Mendori. A Study of the Reliability and Validity of Felder-Soloman Index of Learning Styles in Mandarin Version. Published 12 July 2015. Psychology, 2015 IIAI 4th International Congress on Advanced Applied Informatics. DOI:10.1109/IIAI-AAI.2015.284. Corpus ID: 13680615. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Study-of-the-Reliability-and-Validity-of-Index-of-Wang-Mendori/3282cd4cac2428be2c1e98cc26c90c1d7520c4eb on 4 April 2022.

BIOGRAPHY

Dr Syed Uddin lectures in Business Management, Human Resource Management and Organisational Behaviour at UBSS. Formerly, he was a Research Fellow at the Loughborough University Business School in the United Kingdom. He has written many refereed articles that have been published in prestigious academic journals. Syed is a six-time winner of the UBSS Executive Dean's award for 'Outstanding Commitment to Teaching and Learning' and is a recipient of the Vice Chancellor’s Citation Award for outstanding contributions to student learning.