Issue 3 | Article 5

ABSTRACT

The last two years have marked a period of radical change in the higher education sector. The sudden and unexpected move to online teaching and learning required every actor within the sector to approach learning in agile and unexpected ways. Student feedback surveys have indicated a rise in student satisfaction. However, verbal feedback as well as reports in the media suggest an increasingly unhappy student and staff cohort that does not feel a sense of community or real learning achievement. This raises two questions: first, why do the results of quantitative and qualitative research differ? and second, how can we guarantee and standardise student learning outcomes and student satisfaction in blended learning environments?

INTRODUCTION

The global COVID-19 pandemic caused a massive upheaval in the higher education sector globally, requiring an improvised move to online learning and the development of a new, flexible business model. Due to the rapidly changing nature of the pandemic, institutions in the higher education sector have adopted different strategies and responses to the crisis. Reports from students and staff about the impacts of these changes indicate a mixed response. However, earlier research (Loton et al. 2020) suggests that students cannot gain the same experience and quality of learning in an exclusively online environment. This leads one to wonder why the student feedback results and assessment results have been so overwhelmingly positive.

Changes in the higher education sector due to COVID-19

Prior to COVID-19, senior managers in universities and other higher education institutions globally were already pushing for the digitisation of learning, partly because it would allow them to provide higher volume courses to domestic and overseas-based students. Many teaching staff, on the other hand, argued for the continuation of “high quality, low intake” on-campus courses, noting the difficulties in digitising most courses; however, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the hands of many educators.

The shift to online learning following the onset of the pandemic occurred rapidly. In New South Wales, staff were required to digitise face-to-face courses and prepare students for the shift to online learning during a period of only two weeks. The emotional shock caused by this requirement, as well as the mental load from having to quickly change course materials and to learn new programs for online delivery, had a considerable impact on staff and students alike. Loton et al (2020) pointed out that “such a rapid, at-scale shift to online learning is largely unprecedented” and argued that while “a larger base of comparable literature for online learning suggests that when intentionally designed, online learning can perform similarly [to face-to-face learning], the new online learning ecosystem is less than ideal due to the emergency nature of its introduction.”

Distance, blended, and online learning at universities and other higher education institutions have been growing steadily over the past fifty years (Shachar et al, 2010, Means et al. 2013, Loton et al, 2020). There are certain benefits with this approach. Previous studies of fully online learning concluded that students could find this mode to be just as effective as face-to-face learning despite shortcomings such as feelings of isolation and technology gaps. However, the full impact of the disadvantages is still unknown, and one should ask if a student can get the full experience of the higher education student life while being subjected to isolation and technology gaps. Just as some students find that online delivery makes education more accessible, others may miss the loss of social interaction and hands-on learning provided in face-to-face classes.

Further, the factors that determine satisfaction and student performance with face-to-face education also affect online learning. They include “perceived relevance, self-efficacy, and the quantity and quality of content, systems and student-instructor interactions” (Loton et al, 2020). The perceived advantages of online learning – accessibility and self-paced learning - may not outweigh these disadvantages.

Key findings from two providers in Sydney

Many in the higher education sector expected that “the transition to remote delivery [would] have a negative effect on student satisfaction and performance” (Loton et al. 2020). However, student feedback surveys show an increase in both student satisfaction and academic grades (Loton et al, 2020).

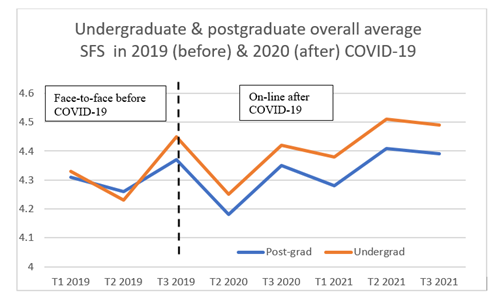

In 2021, student feedback from a Survey (SFUS) conducted by Universal Business School Sydney (UBSS) recorded its highest-ever scores across all items. The overall score for undergraduates was 4.49 out of 5 and for postgraduates was 4.39 out of 5 (see table and graph below). In the Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) Student Experience Survey 2021, UBSS achieved higher rankings than the University of Sydney, University of NSW, and University of Technology Sydney (UTS) in “Overall Positive Student Experience, 81.2%”; “Teaching Quality, 84.7%”; “Learner Engagement, 70.2%”; “Student Support, 79.8%”; and “Skills Development, 82.9%”.

| T1 2019 | T2 2019 | T3 2019 | T2 2020 | T3 2020 | T1 2021 | T2 2021 | T3 2021 | |

| Post-grad | 4.31 | 4.26 | 4.37 | 4.18 | 4.35 | 4.28 | 4.41 | 4.39 |

| Undergrad | 4.33 | 4.23 | 4.45 | 4.25 | 4.42 | 4.38 | 4.51 | 4.49 |

While lower than the scores of UBSS, UTS reported improvements in Overall Experience (70.4%, an increase of 5 percentage points (pp)); Teaching Quality (77.3%, an increase of 4.7pp); Learner Engagement (52.8%, an increase of 5.5pp); and Learning Resources (79.8%, an increase of 4.6pp) (Alexander 2021).

However, these quantitative results are not supported by the qualitative data. For example, when speaking to Study International, the national president of the Council of International Students Australia, Oscar Zi Shao Ong, commented:

We have overwhelming feedback that online studies just aren’t working, . . . Additionally, this is not what international students paid for. They paid for quality, face-to-face education. Further to that, onshore students would have received better support in terms of engagement and social events [than their offshore counterparts] (Study International 2020).

Also, informal feedback received by the author from colleagues and his own experience with online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that many students in online classes are fatigued, frustrated, and disenchanted with the new mode of delivery. Workloads are high and often unmanageable, and while higher education institutions are offering support for students, uptake is often low. The lack of community is felt across all business disciplines and students are unable to engage with their peers to measure and improve their learning.

Analysis of the results

Despite the optimistic picture projected by universities and other higher education providers, it is not lost on the wider community that “internally, the university strategic orientation has been focused on revenue returns and cost efficiency” (Parker 2020: 544). No amount of clever marketing and positive reports can hide the fact that:

Cost efficiencies have included larger class sizes, higher full-time staff teaching loads, greater proportions of casualised and contract teaching and administrative staff, reduced library and support services, decreased maintenance services, reduced budget allowances for staff conferencing and travel and discontinued low enrolment subjects and programs (Parker 2020: 544)

Given the struggles faced by higher education institutions during the pandemic, these cost savings make financial sense. However, it is unclear why, in the constrained teaching and learning environment, universities have been able to report such a marked increase in satisfaction in the quantitative surveys. Parker suggests that:

Accounting’s complicity in this strategic model has been all too evident. Its prominence within the university design archetype can be seen in the forms of tight budgetary control of internal operations; recurrent audits of teaching “quality” controls, (minimised) course pass/ failure rates, (upward promotion of) student satisfaction scores and graduate employment success rates; benchmarking of a myriad of key performance indicators against competitor universities (Parker 2020: 544)

This leads one to consider that perhaps the numbers do not tell the whole story and that survey scores are being accorded unwarranted priority over hands-on experience. While educators need to guarantee and standardise student learning outcomes, the satisfaction and overall happiness of students will be incomplete if they cannot experience a full social life on campus and gain a feeling of belonging to their educational institution.

Perhaps students lowered their expectations of the learning experience when online became the only mode of delivery during the lockdown periods. Students had to accept the transition to online delivery as most people in the community had no choice but to work from home.

Undoubtedly some higher education providers deserve the reported increase in their SFUS scores in 2020 and 2021after moving to a full online learning and teaching platform, because their senior executives seized the opportunity and invested quickly in the required infrastructure. They provided timely training and support to help their academics adapt and adjust to the new online learning environment.

The link between the efforts put forward by higher education providers and the improved student feedback results is, however, yet to be proved.

The way forward

Given the conflicting evidence from student interviews and SFUS outcomes, it is important to find out if there is a disconnect between what students expect to gain and what they actually receive from the full, online-learning mode, and to address any shortcomings that might be revealed. Garrison’s Framework of Social Presence has long been a touchstone for distance learning:

Garrison and Shale (1990) suggested that sustained, contiguous, two-way communication between student and instructor was the appropriate hallmark of distance education because this process allows learners to negotiate and structure personally meaningful knowledge much like the educational transactions that occur in traditional classrooms (Annand 2011: 43)

This suggests that students will only be satisfied with online learning if it is open and communicative. Sustained and continuous communication, and the formation of interactive online and in-person cohorts, will be necessary if we are to treat our students as peers, not as numbers. It is not clear that an already overburdened and highly casualised workforce is up to this task.

CONCLUSION

It is plausible that the debate about whether online or face-to-face delivery produces the better student experience will become irrelevant as a new model of teaching and learning evolves that attempts to incorporate both. As higher education institutions re-activate their campuses in 2022 and encourage students to return to on-campus classes, they are also catering to a growing offshore/online market. The Australian border reopening from 21 Feb 2022 should encourage many international students to return to campus – if this is made attractive to them through utilisation of the “free space” created by increased digitisation of lectures. Courses that were previously offered face-to-face are now being offered in parallel online and face-to-face courses and in hybrid models (where students can take a given class either online or on campus). This has numerous accessibility benefits as staff and students can choose the mode of delivery that best suits them.

It will be interesting to view future survey findings on the outcomes of these different modes of learning; however, we need to agree first on what “success”, “quality of learning”, and “engagement” mean to us as institutions. Within the Community of Inquiry framework (Garrison 2017), the Social Presence, Cognitive Presence and Teaching Presence might still be applicable for good teaching and learning – that is, consideration of how to ensure that offshore, hybrid learning, and flexible educational concepts do not end up being “disconnected”.

REFERENCES

Alexander, S., (2021), Teaching and Learning, 21-39, University of Technology, Sydney, 5 Nov 2021.

Annand, D. (2011), Social Presence Within the Community of Inquiry Framework. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 12, no. 5, Athabasca University Press (AU Press), 2011, pp. 40–56, doi:10.19173/irrodl. v12i5.924.

Baker, J. (2021), Sydney Morning Herald Retrieved from https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/campuses-are-reopening-but-will-students-want-to-return- 20211126-p59cmm.html.

Department of Education and Training (2021), the Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT), Student Experience Survey retrieved from www.qilt.edu.au.

Dimmock J., Krause A., Rebar A., & Jackson B., (2022), Relationships between social interactions, basic psychological needs, and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic, Psychology & Health, 37:4, 457-469, DOI: 10.1080/08870446.2021.1921178.

Garrison, D.R., (2017), E-learning in the 21st Century: A Community of Inquiry framework for Research & Practice, 3rd ed., New York & London, Routledge.

Loton, D., Parker, P., Stein, C. and Sally Gauc (2020) Remote learning during COVID-19: Student satisfaction and performance (now updated with data going to November 2020). https://doi.org/10.35542/osf.io/n2ybd.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., & Baki, M. (2013). The effectiveness of online and blended learning: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teachers College Record, 115(3), 1-47.

Mok, K.H, and Montgomery C., (2021) Remaking Higher Education for the post‐COVID‐19 Era: Critical Reflections on Marketization, Internationalization and Graduate Employment. Higher Education Quarterly, vol. 75, no. 3, Wiley Subscription Services, Inc, 2021, pp. 373–80, doi:10.1111/hequ.12330.

Ong, O.Z.S., (2020), Study International 2020 retrieved from https://www.studyinternational.com/news/international-students-returning-to-australia/.

Parker, Lee D., (2020) Australian Universities in a Pandemic World: Transforming a Broken Business Model? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, vol. 16, no. 4, Emerald Publishing Limited, 2020, pp. 541–48, doi:10.1108/JAOC-07-2020-0086.

Shachar, M. and Neumann, Y. (2010) Twenty years of research on the academic performance differences between traditional and distance learning: Summative meta-analysis and trend examination. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 6(2).

West, A., (2021), Surveys, Message from the Dean #125, UBSS, 15.12.2021.

Zhou, N., (2021), Student Satisfaction at Australia's Universities Drops to All-Time Low in 2020. The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 19 Mar. 2021, retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/mar/19/student-satisfaction-at-australias-universities-drops-to-all-time-low-in-2020.

BIOGRAPHY

Harry Tse is an Assistant Professor at UBSS and a Lecturer for the Economics Group, Business School, at the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS). Prior to joining the Business School at UTS, he was Head of the Economics & Statistics Department at UTS: Insearch. Harry has written two well-known textbooks on Economics (one published by Pearson and the other by McGraw-Hill) as well as 14 peer-reviewed journal articles and 11 conference papers.