Issue 3 | Article 2

Abstract

The legitimacy of B-Schools (Business Schools) and their value in society have long been debated by business scholars and practitioners. Recent global phenomena and technological trends such as COVID-19 and the acceleration of the digital revolution have raised new questions about the roles played by business schools in helping society and industries transit to a sustainable future. In this article, the authors contribute to this debate by using the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education (UNPRME) as a holistic framework to make two points. First, responsible business education as delivered by future B-Schools cannot be separated from global phenomena like the global pandemic caused by the spread of the COVID-19 virus. Rather, B-schools must play a more active role in mitigating the adverse effects of such phenomena on society through partnerships and responsible leadership education. Second, advanced technologies and the digital revolution are creating a landscape in which a new generation of technology-driven and responsible B-schools can form and thrive to train tech-savvy, responsible graduates.

A business school's value proposition

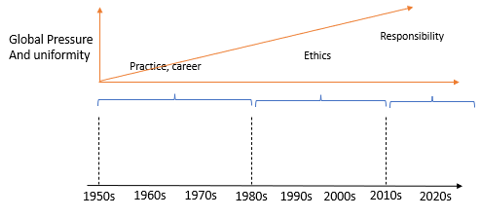

Over the last few decades, the value proposition of a business school has attracted considerable scholarly attention, perhaps because business schools stand at the interface of a variety of conflicting economic, technological, social, and cultural forces (Starkey and Tempest, 2016). As a result, their role and purpose have been surrounded by controversy. For instance, Ventin (2000) eloquently describes business schools as a necessary evil in the educational system and Simon (1967) labels them as a problem in organizational design. In a quest to better understand how business schools of the future, in particular in Australia, can reduce controversy and make a more meaningful contribution to society, the authors surveyed the literature on the history of the value proposition for business schools and identified three phases which are illustrated in Figure 1. Not only is each phase distinct in its core value but also as we move from phase one to phase three, the global pressure to adopt a uniform agenda for an overall universal value proposition of business schools increases.

Figure 1: Evolution of value proposition of B-schools (Source: Authors' creation)

The first stage began in the 1950s and ended in the 1970s. It focused on the primary role of business schools as professional schools. Bach (1958) perceptively argued that “business education should be focused on training men not for the business world of today but for that of tomorrow-for 1980, not for 1958”. Similarly, Simon (1957) urged business schools to offer managers a science-based education they can readily apply. Gutteridge (1973) highlighted the importance of including career-building practical content in the business schools’ curricula.

The second phase ran smoothly from the 1980s into the first decade of the 21st century. Its primary focus was ethics and social responsibility. Dunfee and Roberston (1988). stressed the salience of including ethics in business education. Stead and Miller (1988) argued for an emphasis on training students to be more socially aware. Piper (1989) also called for an increase in students’ sense of responsibility. Benton (1993) argued for incorporating environmental courses into business schools’ agenda. Vroom (1997) discussed the role of psychology in training responsible managers.

Despite these debates and considerable effort to action them, numerous corporate scandals prompted many to question the value of business schools and criticised them for “doing a bad job of meeting the needs of their students and industry for effective education and relevant knowledge” (Pfeffer & Fong, 2004, p. 1502). Some argued that this was partly because business school curricula contain irrelevant or even bad theories, which destroy good management practices (Ghoshal, 2005), causing them to fail to realise their primary purpose of producing professional managers”(Rousseau, 2012, p. 600).

The third phase began in the early 2010s. It tried to address previous concerns by placing greater emphasis on training future-proof managers (Kaplan, 2018) and reinforcing the systematic and methodical inclusion in curricula of a wide range of responsible management practices (Morsing, 2022). It culminated in 2017 when the United Nations (UN) mandated a global agenda known as the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education (UNPRME) as an initiative to raise the sustainability profile of business schools around the world (Morsing, 2022).

Recent phenomena, such as the global pandemic caused by the outbreak of COVID-19 and the rapid growth of digital technologies, place unprecedented pressure on business schools to maintain their relevance by demonstrating a capacity to train responsible managers who are capable of taming digital technologies to tackle unforeseen challenges. Using the UNPRME framework, the authors discuss ways that business schools can transform challenges posed by developments such as COVID-19 and disruptive digital technologies into opportunities for responsible management education.

What are the UN's principles of responsible management education?

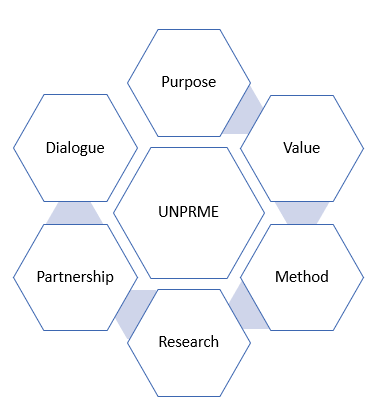

The UNPRME has 6 principles as illustrated in Figure 2: (1) Purpose refers to a commitment to develop students who are future generators of sustainable value for business and society at large and to work for an inclusive and sustainable global economy; (2) Value refers to a commitment to incorporate values of global social responsibility into academic activities, curricula, and organizational practices; (3) Method is about a commitment to design and develop educational frameworks, materials, processes, and environments that enable effective learning experiences for responsible leadership; (4) Research pertains to a commitment to engage in conceptual and empirical research that advances our understanding of the role, dynamics, and impact of corporations in the creation of sustainable social, environmental, and economic value; (5) Partnership relates to an increase in interactions with businesses and managers to better understand real world challenges in meeting social and environmental responsibilities and to explore joint approaches to meeting these challenges; and (6) Dialogue refers to a commitment to facilitate and support dialogue and debate among educators, students, businesses, governments, consumers, media, civil society organisations and other interested groups and stakeholders on critical issues related to global social responsibility and sustainability.

Figure 2: Principles of UNPRME (Source: Authors' creation based on notes from PRME (principles for responsible management education)

The COVID-19 pandemic, unprme, and the business school value proposition

The COVID-19 global pandemic was a once-in-a-generation, black-swan event that affected the global economy in many ways and it is not an exaggeration to say that it crippled the global education system including business schools that rely heavily on international students and work force mobility (Krishnamurthy, 2020). Not only does the road to recovery require an unpresented collaboration between governments, industries, and societies but also warnings have been made that another pandemic may be imminent. Business has a huge opportunity to change the world (Morsing, 2022). Therefore, a responsible business school as outlined by UNPRME has a crucial role to play in taking advantage of this opportunity by preparing the business for, and helping them respond better to, future pandemics.

Business schools should focus on training students who are intellectually and psychologically capable of making effective decisions in the face of crises. This can be manifested in understanding how to collaborate with affected social groups, how to mitigate supply-chain disruptions, and how to allocate resources efficiently when a new crisis is unfolding. Lessons from COVID-19 on vaccine distributions, supply-chain failures, organisational restructuring, business-model innovations in time of uncertainty, value co-creation with local communities, and methods of collaboration with other stakeholders should be converted into case studies and incorporated into subjects. In addition, business schools should encourage staff and students to research the effects of the pandemic on various aspects of business and promote research that outlines innovative methods to manage such crises. Finally, business schools should nurture more collaborative arrangements with other stakeholders such as public health institutes, pharmaceutical companies, and research agencies to develop frameworks, mechanisms, and procedures aimed at preventing and managing health and other crises.

The digital revolution, unprme, and the business school value proposition

The digital revolution is another force that is undermining the relevance of traditional business school models in the global education system. In its broadest sense, the digital revolution refers to the revolutionary forces of new digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, the internet of things, machine learning, and blockchain (Hantrais eat al., 2021; Jawad, Naz, & Maroof, 2021). Universities and business schools alike have always played a fundamental role, not only in teaching younger generation to adopt new technologies, but also in creating a fertile landscape in which new technologies emerge, thrive, and eventually replace old ones (Wissema, 2009).

In the context of higher education, the digital revolution and its associated technologies have two distinct features. First, they have disrupted the ways that teaching and learning are carried out. Advanced learning analytics and new teaching platforms, technologies, and tools have created new opportunities and challenges for both instructors and students such as online, remote, and virtual teaching/learning (Doherty & Stephens, 2021, Kozak, Ruzircky, Stefanovic, & Schinder, 2018). Second, they have created a demand for new skills, which universities (including business schools) must prepare to meet. The pressure on universities to address this demand is constantly rising. Many universities struggle to keep up with the demand but others have strategised ways to stay ahead of the game (Baygin, Yetis, Karakose, & Akin, 2016; Beech, 2018). This is a case of technological forces combining with survival of the fittest in the higher education sphere Wissema, (2009) calls this phenomenon a three-stage evolution from medieval universities to science and technology universities to high-tech entrepreneurial universities. Strielkowski (2020) extends this by adding a fourth stage, called digital and online universities.

As discussed, B-schools either as part of larger universities or as independent higher education institutions play a key role in this evolution. UNPRME offers important insights into how B-schools can succeed. For instance, purpose-driven B-schools must demonstrate an organizational commitment to develop tech-savvy students who can use new technologies to generate sustainable value for business and society. Analogously, B-schools must invest in research that taps into the potential of new technologies to address contemporary societal and environmental issues. Faculty as well as student research on issues such as green-supply chains, green and sustainable marketing and branding, as well as new financial technologies are a few examples of such needed research. Similarly, partnership with new sustainability-oriented ventures, high-tech start-ups, and larger organisations which are adopting sustainable and green business models, co-developing content with them, adding their stories to learning materials, co-creating case studies with them, and having their employees and entrepreneurs as speakers in classrooms can boost B-schools’ capacity to co-evolve with new digital technologies in a sustainable and responsible way.

Remarks at the intersection

In this article, the authors have argued that the COVID-19 pandemic and the digital revolution are two disruptive forces that have profoundly challenged the traditional B-school business model. Future B-schools must embrace digital technologies and generate graduates who are prepared for future pandemics and other large-scale global crises. As such, future B-schools will be high-tech digital institutions that aim to train students who can prevent and respond to unforeseen crises with innovative methods that are responsible, ethical, and sustainable. The authors’ argument is based on UNPRME, which is a set of guiding principles aimed at helping B-schools succeed in the global quest to create a sustainable work economy. The authors also discussed some ways in which B-schools can incorporate UNPRME into their value proposition.

Not only have digital technologies played a crucial role in enabling B-schools to respond reasonably successfully to the COVID-19 pandemic, but they are also playing a fundamental role in paving the way to post-pandemic recovery for B-schools. Therefore, the last point the authors make is that the sweet spot for creating value in the current situation is the intersection of pandemic preparation and the utilisation of revolutionary digital technologies. Applying UNPRME to this centre of percussion suggests that future B-schools’ key role should revolve around generating graduates who are skilled at predicting, preventing, and responding to large-scale crises using latest technologies. This can be achieved in multiple ways such as: (1) investing in programs that promote formation of new and responsible technologies; (2) nurturing collaborative work that is sustainability oriented and responsive to stakeholder needs across sectors; and (3) developing pedagogical and research methods and frameworks that foster a better and more responsible education system using new technologies that are sustainable and responsible. The authors encourage readers to consider these suggestions as a starting point for a fruitful discussion on how future high-tech and digital B-schools can use UNPRME to make more meaningful contributions to a sustainable global economy.

References

Bach, G. L. (1958). Some observations on the business school of tomorrow. Management Science, 4(4), 351-364.

Baygin, M., Yetis, H., Karakose, M., & Akin, E. (2016). An effect analysis of industry 4.0 to higher education. Paper presented at the 2016 15th international conference on information technology based higher education and training (ITHET).

Beech, S. E. (2018). Adapting to change in the higher education system: International student mobility as a migration industry. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(4), 610-625.

Benton, R. (1993). Does an environmental course in the business school make a difference? The Journal of Environmental Education, 24(4), 37-43.

Doherty, O., & Stephens, S. (2021). The skill needs of the manufacturing industry: can higher education keep up? Education+ Training.

Dunfee, T. W., & Robertson, D. C. (1988). Integrating ethics into the business school curriculum. Journal of Business Ethics, 7(11), 847-859.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(1), 75-91.

Gutteridge, T. G. (1973). Predicting career success of graduate business school alumni. Academy of Management Journal, 16(1), 129-137.

Hantrais, L., Allin, P., Kritikos, M., Sogomonjan, M., Anand, P. B., Livingstone, S., . . . Innes, M. (2021). Covid-19 and the digital revolution. Contemporary Social Science, 16(2), 256-270.

Jawad, M., Naz, M., & Maroof, Z. (2021). Era of digital revolution: Digital entrepreneurship and digital transformation in emerging economies. Business Strategy & Development, 4(3), 220-228.

Kaplan, A. (2018). A school is “a building that has four walls… with tomorrow inside”: Toward the reinvention of the business school. Business Horizons, 61(4), 599-608.

Kozák, Š., Ružický, E., Štefanovič, J., & Schindler, F. (2018). Research and education for industry 4.0: Present development. Paper presented at the 2018 Cybernetics & Informatics (K&I).

Krishnamurthy, S. (2020). The future of business education: A commentary in the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic. J Bus Res, 117, 1-5. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.034

Morsing, M. (Ed.) (2022). Responsible Management Education: The PRME Global Movement. New York, NY, USA: Routledge

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. (2004). The Business School ‘Business’: Some Lessons from the US Experience. Journal of Management Studies, 41(8), 1501-1520.

Piper, T. R. (1989). Business School Mission: Increasing Students' Sense of Responsibility. Educational Record, 70(2), 26-28.

Rousseau, D. M. (2012). Designing a Better Business School: Channelling Herbert Simon, Addressing the Critics, and Developing Actionable Knowledge for Professionalizing Managers. Journal of Management Studies, 49(3), 600-618.

Simon, H. A. (1967). The business school: a problem in organizational design. Journal of Management Studies, 4(1), 1-16.

Starkey, K., & Tempest, S. (2016). The future of the business school: Knowledge challenges and opportunities. Human Relations, 58(1), 61-82. doi:10.1177/0018726705050935

Stead, B. A., & Miller, J. J. (1988). Can social awareness be increased through business school curricula? Journal of Business Ethics, 7(7), 553-560.

Strielkowski, W. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and the digital revolution in academia and higher education. Working paper: Prague Business School. doi:10.20944/preprints202004.0290.v1

Vinten, G. (2000). The business school in the new millennium. International Journal of Educational Management, 14(4), 180-192.

Vroom, V. H. (1997). Teaching the managers of tomorrow: Psychologists in business schools. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Career paths in psychology: Where your degree can take you (pp. 49–68). NY, USA: American Psychological Association.

Wissema, J. (2009). Towards the third-generation university: Managing the university in transition. London, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

BIOGRAPHIES

Dr Zahra Sadeghinejad graduated with a PhD in management from Macquarie University. She is an active researcher and an award-winning lecturer. Her areas of teaching expertise include marketing, media management, entrepreneurship, and quantitative methods. Dr Sadeghi’s research has been published as book chapters and journal articles and has been presented at prestigious international conferences for which she has received multiple best-paper awards. Dr Sadeghi is currently a lecturer at the Universal Business School Sydney (UBSS), Central Queensland University (CQU), and the International College of Management Sydney (ICMS).

Dr Zahra Sadeghinejad graduated with a PhD in management from Macquarie University. She is an active researcher and an award-winning lecturer. Her areas of teaching expertise include marketing, media management, entrepreneurship, and quantitative methods. Dr Sadeghi’s research has been published as book chapters and journal articles and has been presented at prestigious international conferences for which she has received multiple best-paper awards. Dr Sadeghi is currently a lecturer at the Universal Business School Sydney (UBSS), Central Queensland University (CQU), and the International College of Management Sydney (ICMS).

Dr Arash Najmaei holds a PhD in strategic management and entrepreneurship from Macquarie University. He is currently working as an associate director of analytics and teaching at various universities. His teaching interests include business research methods, strategic management, entrepreneurship, organizational change, and media management. Dr Najmaei’s research has been published in several journals and research books and presented at international conferences. He has also received three best-paper awards for his research in entrepreneurship and research methods.