Issue 2 | Article 7

Abstract

The use of SETs for evaluating instructors and courses is a controversial, sometimes political, and often hotly debated issue in many college and university staffrooms. Some instructors and administrators argue that the information provided by SET ratings and comments helps them perform their roles more effectively, while others (mainly instructors) maintain that the instrument has biases and other weaknesses that make its use counterproductive. The effectiveness of the instrument also depends on the participation rate, which appears to be substantially lower for online learning. This article discusses the advantages and disadvantages of SETs and makes suggestions on how they can best be used in both face-to-face and online learning environments.

Introduction

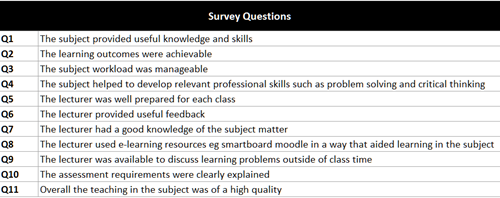

Student Evaluations of Teaching (SETs) is an instrument used by education providers to collect and organise data on student ratings of instructors and courses. At UBSS, we refer to them as SFUs (Student Feedback on Units). Typically, the ratings are collected toward the end of the teaching period (e.g., a trimester), often in the final revision class when most students are likely to be present. The data are obtained through structured surveys that may be paper based but increasingly are online (e.g., through Survey Monkey). The surveys require students to rate characteristics of their instructor (such as how well prepared for class; feedback provided; use of technology; availability outside of class; and overall quality of teaching) and the course (e.g., its usefulness, learning outcomes were achievable; workload manageability; and clarity of assessment). The ratings are usually on a 7-point or 5-point Likert scale where, for the latter, 1 might indicate “Strongly disagree”, 2 “Disagree”, 3 “Neither agree nor disagree”, 4 “Agree”, and 5 “Strongly agree”. Students are also encouraged to provide open-ended comments, where they give their opinions on the teaching and the course using free-form text. The responses to the structured survey are used to compute means for each and all characteristics of each instructor and each course, as well as means for all instructors and all courses across programs and faculties. Some institutions also identify median values for the overall means of instructors as well as other measures designed to provide useful information for users.

UBSS has been collecting SFUs (SETs) in a systematic way since 2016 using a standard set of 11 questions -

Relevant SET outputs (statistical measures and comments) are made available to instructors after exam results for the trimester have been processed. Each instructor receives a personalised file showing their mean scores for individual items as well as an overall score for their teaching and their course. They are normally provided with the faculty means – and sometimes the medians - for teaching and the course. A few institutions also give the percentile score for the instructor’s teaching, probably the best indicator of their performance relative to those of their colleagues.

Selected SET ratings are also normally provided to administrators, who use them as an input into decisions about curricula and courses and about hiring, promotion, tenure, merit-increases, and training for instructors. Most higher education providers have a standard for SET ratings against which the results for individual instructors and courses are compared. A typical standard for a 5-Likert SET might specify that a rating in the range 4.6 – 5 is Outstanding, 4.3-4.5 is Very Good, 4.0-4.2 is Satisfactory, and Below 4 is Unsatisfactory. The bottom category might trigger corrective responses such as training support for the instructor, or modification of the content or design of the course.

History

Formal SET ratings have been collected for about a century. In the 1920s, Herman Remmers (Purdue University) and Edwin Guthrie (University of Washington) independently developed SET instruments with the intention of providing feedback to instructors on how students viewed their teaching (Stroebe, 2020). Administrators quickly saw the potential of SET ratings for increasing student engagement, improving courses and teaching, and evaluating the performance of instructors seeking employment, promotion, tenure, or pay rises. As a result, the proportion of US colleges using SETs increased to 29% in 1973, 68% in 1983, and 94% in 2010.

Evaluation

SETs and students

Students undertake tertiary studies for a variety of reasons, such as gaining the formal qualifications needed to enter a particular profession and the specific knowledge and skills needed to be successful in that profession. The SET process (collecting, organising, disseminating, and evaluating data on student ratings) provides them with a convenient and anonymous vehicle for expressing their approval or disapproval of part or all of the learning opportunities being provided to them and for making suggestions that might improve the offering in later trimesters.

Since their studies extend over several years, and those years can be among the most challenging in their lives, students also want their educational experience to be as convenient and enjoyable as possible. Many studies judge the validity of SETs by looking only at how well they measure student learning. However, student satisfaction is a legitimate goal and for many students may be an important mediating variable between institutional resources and student learning.

Not all students place value on the opportunity to provide feedback, as is indicated by the low natural participation rates and the efforts that education providers make to increase participation. This might be because students are generally satisfied with the offering, think their input will not have a significant impact, or don’t have any interest in the future performance of the education provider. However, since the cost to students of participating in the data collection process is minimal and many students do value having a voice, it is likely that the net benefit to those who participate exceeds the net cost to those who see little or no personal value in the exercise.

Sets and instructors

Instructors want to be good teachers. For this, they need feedback on what is working and what needs to be improved. Students are well qualified to address most statements on a typical SET form since they have been exposed to the instructor’s content, teaching aids, and methods of delivery for almost a whole trimester (traditionally about 12 weeks) by the time the ratings and comments are collected. They have also acquired a framework for comparing teaching and courses by attending classes taught by a variety of other instructors, both concurrently and over many preceding years, and from discussing and comparing their experiences with other students (Arreola, 1994). Many higher education institutions also provide a formal process of peer review, in which a colleague observes a class and discusses their findings with the instructor after the class has concluded. Such feedback can be a useful supplement to SETs information, especially in relation to such matters as the instructor’s knowledge of course content. However, peer reviews cover only one class, this class may not be fully representative since the instructor normally knows when their colleague will be attending, and the post-class discussion may not be completely frank if the review process is reciprocal, or friendship is involved.

Most instructors value their professionalism and examine carefully all their ratings and comments. A typical approach to the receipt of SET outputs was outlined by Vanderbilt’s Emeritus Professor of Psychology, Kathleen Hoover-Dempsey (who was also a recipient of the university’s highest teaching honour, a Chair of Teaching Excellence). During an interview, she stated “I read every comment and find the comments extremely useful in thinking about and improving my own teaching… Overall, I think the numerical ratings are really important, but you often need to analyse students’ comments in order to remedy some of the concerns that may underlie lower ratings.” (Vanderbilt, 2021).

A second benefit for the more conscientious and better teachers is that their superior performance is made known to administration, which can take the student feedback into account when making decision about promotion and pay.

Analysis of the usefulness of SETs outputs relate mainly to their reliability (internal consistency) and validity (accuracy). Reliability does not seem to be a major concern among researchers. There are, however, vigorous debates about their validity.

Studies conducted prior to the 1990s suggested that SET ratings were reasonably valid measures of teaching effectiveness, with the latter variable generally being measured by end-of-period exam results. For example, a major study by Cohen (1981) showed a correlation of 0.43 between ratings and student performance in common final exams in multisectional classes. Also, Marsh (1987) found that:

“Ratings are 1) multidimensional; 2) reliable and stable; 3) primarily a function of the instructor who teaches the course rather than the course that is taught; 4) relatively valid against a variety of indicators of effective teaching; 5) relatively unaffected by a variety of variables hypothesised as potential biases; and 6) seen to be useful by faculty …” (Marsh, 1987)

Later studies noted that some of the research undertaken in the 1960s through the 1980s involved researchers who worked for or had been funded by companies developing and selling SET instruments and that this would likely have influenced their results. Other studies have observed that both instructor and course ratings tend to be lower (less favourable) for classes that are small and for courses that are in the hard sciences, are core (versus elective), are out-of-major, and are entry-level. However, the differences in most cases are small (Theall, 2002). Studies have also shown a positive correlation between ratings and grades, and critics of the SETs mechanism have suggested that this could be due to instructors deliberately providing higher grades in the expectation that students will reward them with higher ratings. Since grades are not announced until after the exams are graded, this is problematic. It is just as likely that better teachers both get higher SET scores and produce more learning, with the latter generating the higher grades.

Of more concern is biases relating to race and gender. Skin colour should have no effect on teaching ability, but American studies show that teachers who are white tend to get higher teacher ratings than those of darker complexion. Instructors who are black receive the lowest ratings. Studies on the role of gender are inconclusive, with some studies showing that male students tend to give higher ratings to male instructors and female students tend to provide higher ratings to female instructors, and situational factors (such as female instructors having relatively more large, entry-level courses) explaining some lower ratings for female instructors.

Research also indicates that popularity leads to higher ratings. This is more of a concern for those who feel that student satisfaction is not an appropriate goal, or that popularity detracts from student learning. Further, some instructors might be popular because they are good teachers. Just as researchers funded by SET companies will tend to produce results that favour a strong, positive relationship between teacher ratings and student learning and satisfaction, so researchers like Marilley who claim that “New evidence must be found to overturn the view that evaluations reveal who really knows how to teach …” (Marilley, 1998) will tend to find evidence that casts doubt on the validity of positive ratings.

SETs and administrators

Administrators (such as faculty deans and program directors) use SET ratings as an input into decisions about curricula and courses and about hiring, promotion, tenure, merit-increases. and training for instructors. Well-managed institutions also use many other sources of input, such as consultation with industry bodies and reviews of offerings by competing providers for courses, and recommendations by program managers for matters affecting instructors. Capable deans regard SET ratings as only one of many indicators of teaching performance. Some researchers claim that many deans rely solely on SET ratings and that because the latter are imperfect they should be abolished (Stroebe, 2016). This approach would leave some deans with no information, and others with less information, on which to base decisions. A better approach would be to work on organisational structure, recruitment, and training at the managerial level and widen the types of information available to mangers when they are making decisions about employment details of instructors.

Recommendations

- Like every other educational, psychological, or sociological instrument, SET ratings are imperfect, and should not be sole inputs to policy decisions affecting students, courses, and instructors. They should, however, be one of the inputs;

- The institutional person that interacts with students during the SETs data collection process should not be the class instructor. Using a person from administration increases the trust of students in the anonymity of the evaluation process;

- Data should be collected from students during a regular class when attendance is expected to be high (e.g., commencing 30 minutes into the revision class at the end of the trimester). Sufficient time (e.g., 20 minutes) should be allowed so students can think carefully about their ratings and comments;

- Special attention should be paid to increasing student participation of online students in the SET process, which tends to be about half the rate for onsite students (Vanderbilt, 2021);

- The person administering the survey should explain to students the importance of the evaluations, especially for future students. They should emphasise that the surveys are confidential, that only summary information will be made available to the instructor, and that this information will not be available until all assessments for the course have been completed;

- The personalised SET results should be provided to each instructor as soon as possible after student assessments have been finalised and preferably before the start of the following trimester;

- When evaluating feedback, instructors should take into account both their own situation and the course characteristics. They need to be aware that SET scores tend to be slightly lower for large classes in courses that are quantitative, entry-level, and out-of-major;

- Instructors should beware of outliers. In very large classes there will always be a generous angel and an angry devil. A well-loved dean at Nottingham University used to advise new staff that it is not unusual to see a comment like “Professor X is by far the best teacher I have ever had. I wish he/she could deliver all the courses here.” followed by “I have never been so bored in my entire life. Time literally stands still during his/her classes” Rather, pay attention to the most frequently mentioned areas for improvement. For new instructors, this will often require providing more time for student participation;

- Instructors should discuss their evaluations with a trusted colleague. Studies indicate that instructors who do this are more likely to receive higher SET scores in the following teaching period;

- Instructors and administrators should be trained in the correct interpretation and appropriate use of SET data. A study by Theall and Franklin (1989) showed a strong correlation between both the ability to interpret relevant statistical data and knowledge of common differences and positive attitudes toward the use of SETs for evaluation purposes;

- Administrators should use SET ratings as only one input into the evaluation process for courses and instructors;

- Limit the number of questions to ensure appropriate focus and maximise completion; and

- When size permits, higher education provide should consider establishing a Centre for Teaching Excellence that provides general and individual support on course design, delivery, and assessments.

References

Arreola, R. (1994). Developing a Comprehensive Faculty Evaluation System. Boston: Anker.

Cohen, P. (1981). Student Ratings of Instruction and Student Achievement: A Meta-analysis of Multisection Validity Studies. Review of Educational Research.

Theall, M, and Franklin, J. (2002) Looking for Bias in All the Wrong Places: A Search for Truth or a Witch Hunt in Student Ratings of Instruction? https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ir.3

Marilley, S. (1998). Response to ‘Colloquy’. Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/colloquy/98/evaluation/09.htm

Marsh, H. (1987). Students’ Evaluations of University Teaching: Research Findings, Methodological Issues, and Directions for Future Research. International Journal of Educational Research.

Stroebe, W. (2016). Student Evaluations of Teaching Encourages Poor Teaching and Contributes to Grade Inflation: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01973533.2020.1756817

Vanderbilt (2021). Student Evaluations of Teaching. https://www.vanderbilt.edu/course-teaching-evaluations/evaluation_reevaluation.php

Biographies

Angus Hooke is Professor, Senior Scholarship Fellow, and Co-Director of the Centre for Scholarship and Research (CSR) at UBSS. His earlier positions include Division Chief in the IMF, Chief Economist at BAE (now ABARE), Chief Economist at the NSW Treasury, Professor of Economics at Johns Hopkins University, and Head of the Business School (3,300 students) at the University of Nottingham, Ningbo, China. Angus has published 11 books and numerous refereed articles in prestigious academic journals.

Emeritus Professor Greg Whateley is the Deputy Vice Chancellor, Group Colleges Australia (GCA). Formerly, he was Chair of the Academic Board at the Australian Institute of Music and Dean of the College at Western Sydney University. He has been keenly interested in alternative modes of delivering education since 2000 when he co-invented ‘The Virtual Conservatorium’ and has since found himself involved, some twenty years later, in the development of the virtual school.

Anurag Kanwar is Director of Compliance and Continuous Improvement at Group Colleges Australia (GCA), Executive Secretary of the GCA Board of Directors, and a member of the UBSS Academic Integrity Committee, Audit and Risk Committee, and Workplace Health and Safety Committee. Anurag is also a practicing lawyer in NSW specialising in the areas of corporate governance and risk. Anurag is a prolific commentator on matters relating to international education on LinkedIn with over 5000 followers.