Issue 2 | Article 15

Abstract

The traditional mode of delivering tertiary education has focused on face-to-face classes delivered to increasingly diverse global student cohorts. COVID-19 forced most providers to move abruptly to online delivery and, in countries exporting education, to smaller cohorts as international borders were closed. The author of this article argues that online delivery is here to stay, and that providers should learn from marketers how to make their product more attractive to students in order succeed in a more competitive education environment.

Introduction

The tertiary education industry is experiencing considerable change. Higher education providers in leading exporting countries such as the United States and Australia are catering to more socially and culturally diverse student populations than ever before, due largely to increasing numbers of foreign students (Jude & Ryan, 2005). In addition, the COVID–19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns forced most providers to (temporarily at least) abandon face–to-face (F2F) classes in favour of wholly online delivery. However, as is often the case, the recent, abrupt changes bring not only new challenges but also new opportunities.

These new opportunities require moving from the traditional strategy of sage-on-the-stage, F2F delivery to a more engaging online strategy that will enhance the student learning experience. Lecturers, the most visible stakeholders in universities, will have a key role to play. They will need to redesign resources and delivery strategies to engage students who are now mostly millennials (born between 1981 and 1996 and so comfortable with online technologies) or members of generation Z (born after 1996, and so have never been offline). Lecturers also often play the role of customer service staff as most of the time they are the most frequent point of contact with students.

The diverse cultural backgrounds, different education experiences, and wide age range of globally sourced students may create emotional barriers between lectures and students, (Yahanpath & Yahanpath, 2012). However, the barriers can be removed by providing more interactive online classes, better engagement with students, and strengthening collaborations that create new and better learning experiences.

The challenge, then, becomes addressing the needs of both lecturers and students within the context of a tertiary education sector that is becoming ever more pressured, and resource constrained. The marketing discipline may have some strategies to offer. According to The American Marketing Association, “Marketing is the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large.” (Kotler & Keller 2015). This article explores new concepts for delivering engaging, collaborative online learning experiences in tertiary education from a marketing perspective.

Transition from F2F to online learning

Before the COVID–19 pandemic, F2F learning was the preferred mode of delivery from the perspective of Australian universities. Many lecturers were totally dependent on PowerPoint (PPT) slides to support their oral presentations in lectures. Also, because of their long histories and the difficulties facing new entrants, universities were able to charge premium prices for their services. However, border closures in early 2020 resulted in a significant decline in both local and international student intakes and the consequent decline in revenues has placed tremendous pressure on university finances. As a result, to compete and stay relevant, universities need to change their business model.

According to Kotler & Keller (2015), undifferentiated, differentiated, concentrated, and micromarketing strategies should all be considered. An undifferentiated marketing strategy, or mass marketing, entails creating a single message for an entire audience. Its counterpart in higher education is F2F learning, where most lecturers are wholly dependent on PPT slides to support their oral presentations. It is a one-size-fits-all approach and has long been the preferred strategy for most lecturers. A differentiated marketing strategy involves creating different messages for two or more market segments or target groups. Its educational equivalent would be the use of combinations of online quizzes, PPT slides, and recorded lectures to deliver material to students.

Concentrated strategies are blended modes using online delivery features such as quizzes, case studies, and presentations. Blogging and chat box are examples of micromarketing strategies, where lecturers tailor-make online delivery to meet the different needs of individual students. All these strategies can be used by lecturers to increase student engagement. Differentiating their services from those of other education providers will be the main challenge facing higher education institutions in the coming decade.

Moving from undifferentiated to differentiated strategies by focusing on individual student needs using various online tools is the game changer. Online learning has been the norm of education providers for the past 18 months and will remain so in the future. Not only is it cost effective, it also meets the individual needs of students, especially when the online platforms have a wide range of features for engaging students such as blogging, web mailing, and chatting. It also provides students with the opportunity and leisure to study from any location.

Marketing and sales skills emphasise the importance of customer retention and relationship building. Stronger relationships with customers lead to better outcomes for both sellers and customers. Relationship-based sales is cost effective. The same applies to education. Communication and collaboration between the lecturer and student using online platforms helps to deliver messages quicker, promotes better understanding of the needs of students - especially if the students are from overseas – and fosters student engagement. The marketing cost for recruiting and retaining students is high. With international student enrolments currently declining, building relationships in a collaborative way can enable universities to attract and retain more students.

With better online learning platforms and tools, lecturers can more easily engage with students and assess their needs, enabling them to respond quickly to student queries. Some overseas students are reluctant to ask questions in a traditional F2F learning environment due to shyness. Online platforms can break down that barrier and from my experience help students become more highly engaged. Lecturers using online platforms have the tools needed to facilitate engagement better and challenge students’ thinking and learning ability in a more friendly way. Rather than getting offended, students become motivated and then take the initiative in classroom discussions.

The 3 Cs of online learning: communication, collaboration, and commitment

According to Chickering and Gamson (1987), frequent contact between students and faculty during and after lectures is the most important method of motivating and engaging students, particularly during tough times. Connecting and communicating with students enhances their intellectual abilities and encourages them to think about their own values and future study options. It is vital for student motivation and engagement, especially during the transition from F2F to online learning. The lecturer’s empathy and communications with students can reduce students’ stress and anxiety and help them achieve their required learning outcomes.

In marketing, as we move from traditional to digital communication, changes in consumer behaviour are increasing the importance of communicating with customers. Businesses are using online platforms such as social media, email, and blogs to collaborate with customers. Similarly, collaboration is vital in tertiary education to enhance the student learning experience (Fox 2021). It requires knowledge about how collaborative learning can be effectively applied using online platforms and how technology can be optimally utilised to support online learning. The benefits of both are greater collaboration between customers (students) and universities (lecturers) and enhancement of student learning experiences and competencies. It also increases student cooperation, builds commitment towards learning, and increases academic integrity.

Fox (2021) suggested that some of the benefits of online learning in tertiary education are:

- Increased student engagement in the classroom;

- Greater ability to create active learning spaces among students;

- Enhanced student achievement in their academic program;

- Development of necessary skills for future employability;

- More self–individual experiences;

- Better social–emotional learning skills; and

- Greater ability to work in a group environment that increases analytical thinking skills, critical thinking skills, and interactions.

Engaging students with different learning styles

Identifying and understanding the different learning styles of students is a challenging task. It is equivalent to understanding customer needs and wants by gathering relevant buyer information through research. According to Bateman & Snell (2012), the VARK model identifies four types of learner: (1) Visual learners who prefer acquiring information through illustrations such as examples and cues; (2) Auditory learners who would rather listen and are adept at converting spoken instructions into actions; (3) Reading learners who prefer to receive information in the form of text; and (4) Kinetic learners – the learners by doing - who like to figure out answers to questions and solutions to problems themselves using physical feedback cues.

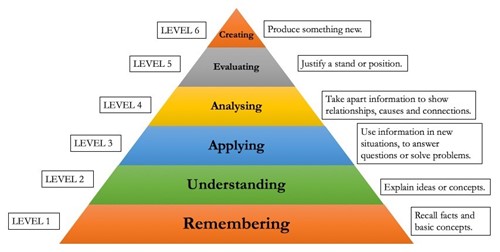

To design appropriate online materials, lecturers first need to understand the learners’ level of thinking. Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956) identifies six levels of learning, from the three lower levels of remembering, understanding, and applying to the three higher levels of analysing, evaluating, and creating.

Fig 1. Bloom Taxonomy 1956.

Level 1 is the most basic learning activity and entails remembering and recalling facts. Level 6 is the highest level, involving creating something new. Lecturers need to determine students thinking levels before designing online delivery resources such as PPT slides, blogs, case studies, and quizzes. They can do this by communicating with and getting feedback from students. Online platforms have the tools needed to implement this process.

When designing class activities, lecturers should frame tasks in ways that encourage students to defend their positions, reframe their ideas, listen to others’ points of view, and articulate their points so they gain a complete understanding both as a group and as individuals. Students tend to be more engaged and learn more when they are exposed to diverse viewpoints, especially those of people from different backgrounds. Lecturers should set tasks that allow students to think about the challenges they may encounter in their lives and help students to build new skills and capabilities. These skills may include:

- Listening to criticism and feedback;

- Public speaking and active listening skills;

- Critical thinking skills; and

- Cooperating with others.

Economics of engaging and collaborative learning experiences

The COVID–19 pandemic has led to changes in the business models of universities and other higher education providers, including a transition from the traditional F2F mode to a highly simulated online delivery method. Many universities have been downsizing staff and consolidating campuses in a more centralised location where lecturers can deliver online classes to larger numbers of students. As noted by Kotler (2020), pricing is the only element in the marketing mix that earns revenue. International students, a major source of revenue, face significant difficulties, including studying in an unfamiliar environment, juggling study and work commitments, and commuting between campus, work, and home. Their choice to study abroad carries risks as well as benefits (Jude & Ryan, 2005). Transitioning to the new business model using online platforms provides enormous benefits to universities and other higher education providers by enabling then to provide more effective learning, increase student numbers, and restore their revenue streams. It also benefits international students by allowing them to study from any location and providing them with access to tools that enhance collaboration, engagement, and learning.

Collaborative and engaging learning helps equip students with the skills and competencies they need for future jobs, including:

- Analytical skills and innovative mindsets;

- Active learning skills;

- Leadership and social skills;

- Knowing how to use technology to enhance skills development;

- Communication skills; and

- Complex critical thinking skills (Whiting 2020).

Conclusions

The future of F2F learning is bleak. From being the sole method of delivery for centuries, it has moved to a partnership role with distance learning and now online learning and may soon be largely replaced by online learning.

The tertiary education sector will continue to face challenges from decreasing international students, rising costs, and increasing competition. University managers and lecturers will need to constantly monitor and update online delivery methods as the needs and wants of students continue to change.

Universities should continue to enhance the relevance and quality of the education they provide students, especially those parts aimed at strengthening employability skills. They can do this by blending online and F2F delivery and by applying key marketing concepts to the ways in which the organise and deliver education.

References

Bateman, T. and Snell, S. (2012). Management: Leading and Collaborating in the Competitive World, 10th ed., Australia: McGraw-Hill.

Bloom, B. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, https://www.google.com/search accessed on 26/10/21.

Chickering, A. and Gamson, Z. (1987). Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ed282491, accessed on 21/10/21.

Carol, J. and Rayan, J. (2005). Teaching International Students. Oxon: Routledge

Fox-Jensen, E. (2021). Collaborative Learning Methods, Tools, Research and Practical Models within a Digital Learning Environment: Ethics, Caring and Sharing Design,’ doi: 10.13140/8622.25308.10881/1.

Kotler, P., & Keller, K. (2016). Marketing Management, 15th edn, Pearson Education, England.

Shantha P. and Shan Y. (2012). Power of ‘Teaching by Walking Around. https://www.ft.lk/Opinion-and-Issues/power-of-teaching-by-walking-around/14-112876, accessed on 21/10/21

Whiting, K. (2020).’These are the top 10 skills of tomorrow’, World Economic Forum.

Biography

Assistant Professor Ajay Kumar lectures in Marketing Management, Organisation Behaviour, Project Management and Strategic Management at UBSS. Previously, he was Sessional Lead Lecturer Central Queensland University. Ajay has professional experience as Business Development Manager at DHL Australia and General Manager Marketing, Sales and Market Research at Post Fiji. His professional memberships include Fellow and Certified Practicing Marketer (FCPM), Australian Marketing Institute; and Member, Institute of Managers and Leaders (IML). In 2021, he was appointed NSW Emerging Marketing Mentor & Judge for AMI Awards, Australian Marketing Institute.