Issue 1 | Article 14

Abstract

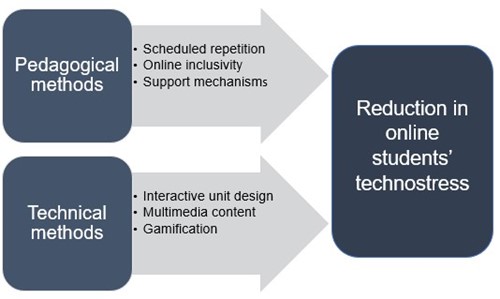

Technostress refers to the stress that is induced by using technology. It leads to depression, anxiety, fatigue, and reduced productivity. Online teaching and learning and their reliance on information technologies produce technostress in students. In an earlier article (Najmaei, 2020), we discussed three technical methods, namely interactive unit design, gamification, and multi-media content, that can help reduce students’ technostress. In this article, we discuss three teaching methods that can reduce students’ technostress, namely support mechanisms (before and after class support, online and offline support), online inclusivity, and scheduled repetition.

Technostress and Online Teaching and Learning

In our earlier article, we defined technostress as the stress induced by one’s inability to adopt new technologies (Ragu-Nathan, 2008). Technostress is a key dark side of technology and if not managed can act as a corrosive force with severe detrimental effects on one’s productivity and psychological wellbeing (Bondanini, 1984). It has been established that online teaching and learning and the need to use a wide range of new technologies are a source of technostress among students (Wang, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has created a new phase of online teaching in which a wider range of students has to adopt online technology. Consequently, increasing attention is being paid to methods and techniques that help educators reduce students’ technostress (Qi, 2019; Upadhyaya, 2020; Wang, 2020). In the first article, we elaborated how we used a research diary technique (Nadin, 2006; Ohly, 2010) to extract three technical methods for reducing technostress. This article follows on with an illustration of three complementary pedagogical methods.

1. Support Mechanisms

The benefits of providing prompt and substantive support are well documented in the literature. Notes in our diary confirm these benefits. Mechanisms such as a mix of online and offline instructional consultation sessions (OICs) (Weay, 2012), before and after class consultations (Penny, 2004), online support communities such as WhatsApp groups, flipped classes where students learn by teaching others (Lewis, 2006), and connecting with students via online platforms such as Skype, telephone, email, and Zoom meetings, not only ensure that learners’ needs are met more effectively but also increase teacher-learner interactions (Martin, 2019; Stickler, 2020). These result in a better experience for learners and a reduction in their technostress.

2. Online Inclusivity

It is well noted that students may feel isolated and disconnected in online courses, and this may affect how they adopt and use technologies to engage in class activities and learn new content (Kebritchi, 2017). The social constructionist view suggests that students and the community within which they interact socially cocreate their identities. Therefore, online students need to develop a shared sense of belonging, purpose and norms in their online classes (Koole, 2014). An inclusive approach to teaching online classes is critical to achieving this goal. Inclusive teaching involves active listening, creating an engaging learning atmosphere, emphasizing students’ uniqueness of identity and ensuring that the students’ need to belong is satisfied (Molbaek, 2017). A strong sense of identity along with belonging to and being a valued member of the knowledge community plays a critical role in effective knowledge building and creates the confidence and motivation required to adopt new technologies (Kebritchi, 2017). Therefore, a didactic approach to online inclusivity is a valuable method for reducing online students’ technostress.

3. Scheduled Repetition

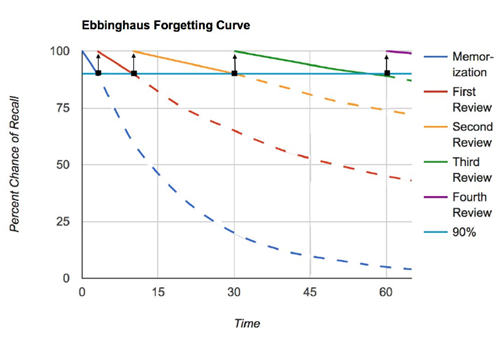

Research suggests that spaced or scheduled repetition of content improves memory, increases learning capacity and reduces stress caused by the pressure to memorize and recall (Dumesnil, 2018). Ebbinghaus (2013)’s forgetting curve offers a theoretical explanation for the role of scheduled repetition in reducing student’s perceived techno-stress. According to Ebbinghaus, the forgetting curve (Figure 1) becomes less steep by each reminder indicating the learner has a better chance of remembering for longer periods of time after each review (Dumesnil, 2018). This lessens technostress by reducing the reliance on and the demand for online technologies.

Figure 1: Ebbinghaus' forgetting curve (Source: Dumesnil 2018)

Concluding Remarks

As noted by Baran and Correia (2014), teachers “may feel uncertain, uneasy, and unprepared for the challenges of teaching online, lacking the tools and conditions they rely on to establish their expertise and teacher persona in the traditional classroom”. Martin et al. (2019) suggested that the field of online learning research offers a ripe opportunity to contribute to both the practice of online instructors and the body of knowledge surrounding effective online learning. Specifically, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, where more classes are being offered online and many teachers have no option but to teach online, learning about a repertoire of skills to use in online classes has significant implications for research and practice. Techniques that we discussed here may help teachers deliver online classes in ways that are less stressful for students and more conducive to learning. Online teaching is the new normal in the world of education and technostress is an inevitable consequence of this phenomenon. Although online students may always suffer some degree of technostress, teachers can help them have a more pleasant online learning experience.

Figure 2 is a schematic summary of the techniques we have proposed in our two articles.

Figure 2: A schematic summary of methods to reduce online students' technostress

References

- Baran, E., & Correia, A.-P. (2014). A professional development framework for online teaching. TechTrends, 58(5), 95-101. doi:10.1007/s11528-014-0791-0

- Bondanini, G., Giorgi, G., Ariza-Montes, A., Vega-Munoz, A., & Andreucci-Annunziata, P. (2020). Technostress Dark Side of Technology in the Workplace: A Scientometric Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(21). doi:10.3390/ijerph17218013

- Brod, C. (1984). Technostress: The Human Cost of the Computer Revolu tion. Addison-Wesley, Readin.

- Dumesnil, D. (2018). The effects of spaced repetition in online education. PhD dissertatio, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology,.

- Ebbinghaus, H. (2013). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Annals of neurosciences, 20(4), 155-156.

- Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and Challenges for Teaching Successful Online Courses in Higher Education. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 46(1), 4-29. doi:10.1177/0047239516661713

- Koole, M. (2014). Identity and the itinerant online learner. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance learning, 15(1), 52–70.

- Lewis, C. C., & Abdul-Hamid, H. (2006). Implementing Effective Online Teaching Practices: Voices of Exemplary Faculty. Innovative Higher Education, 31(2), 83-98. doi:10.1007/s10755-006-9010-z

- Martin, F., Ritzhaupt, A., Kumar, S., & Budhrani, K. (2019). Award-winning faculty online teaching practices: Course design, assessment and evaluation, and facilitation. The Internet and Higher Education, 42, 34-43. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.04.001

- Molbaek, M. (2017). Inclusive teaching strategies – dimensions and agendas. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(10), 1048-1061. doi:10.1080/13603116.2017.1414578

- Nadin, S., & Cassell, C. (2006). The use of a research diary as a tool for reflexive practice. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 3(3), 208-217. doi:10.1108/11766090610705407

- Najmaei, A., Sadeghinejad, Z. (2021). Reducing Students’ Technostress in Online Classes: Three Technical Methods. UBSS Publications Series.

- Ohly, S., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Zapf, D. (2010). Diary Studies in Organizational Research. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(2), 79-93. doi:10.1027/1866-5888/a000009

- Penny, A. R., & Coe, R. (2004). Effectiveness of consultation on student ratings feedback: A meta-analysis. Review of educational research, 74(2), 215-253.

- Qi, C. (2019). A double-edged sword? Exploring the impact of students’ academic usage of mobile devices on technostress and academic performance. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(12), 1337-1354.

- Ragu-Nathan, T. S., Tarafdar, M., Ragu-Nathan, B. S., & Tu, Q. (2008). The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and empirical validation. Information systems research, 19(4), 417-433.

- Stickler, U., Hampel, R., & Emke, M. (2020). A developmental framework for online language teaching skills. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 133-151. doi:10.29140/ajal.v3n1.271

- Upadhyaya, P., & Vrinda. (2020). Impact of technostress on academic productivity of university students. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1647-1664. doi:10.1007/s10639-020-10319-9

- Wang, X., Tan, S. C., & Li, L. (2020). Measuring university students’ technostress in technology enhanced learning: Scale development and validation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(4), 96-112.

- Weay, A. L., & Mohamed, N. F. F. (2012). Online instructional consultation (OICon) model for higher education institution (HEIs). Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 67, 1-15.

Biographies

Dr Zahra Sadeghinejad graduated with a PhD in management from Macquarie University. She is an active researcher and an award-winning lecturer. Her areas of teaching expertise include marketing, media management, entrepreneurship, and quantitative methods. Dr Sadeghi’s research has been published as book chapters and journal articles and has been presented at prestigious international conferences for which she has received multiple best-paper awards. Dr Sadeghi is currently a lecturer at the Universal Business School Sydney (UBSS), Central Queensland University (CQU), and the International College of Management Sydney (ICMS).

Dr Arash Najmaei holds a PhD in strategic management and entrepreneurship from Macquarie University. He is currently working full time as a marketing consultant and teaching part time at various universities. His teaching interests include business research methods, strategic management, entrepreneurship, organizational change, and media management. Dr Najmaei’s research has been published in several journals and research books and presented at international conferences. He has also received three best-paper awards for his research in entrepreneurship and research methods.